The Spider and the Bookcase

– Non-Fiction by Amanda Bloodgood – January 26, 2019

A Spiny Orb Weaver spider has taken up residence in the potted plants next to my back door. It is an odd looking creature with a black and white crab-like shell, minus the claws. I have been watching it for weeks. It works tirelessly building and rebuilding a large, circular web. From the center, about thirty-five strands branch off and extend to an ever widening circle two and half to three feet wide, not including the anchors. It is the classic Halloween web.

As we waited for Hurricane Florence to make landfall, I moved my potted plants indoors to protect them from high winds. I left one out – the one to which a length of silk was anchored. I considered catching the spider and placing it in a jar with holes in the lid just until the storm had passed, but thought better. I didn’t want to kill it with misguided kindness.

The hurricane turned course and took its rage many miles to the south. We were fortunate to feel only its peripheral strength. The spider remained centered as its web bounced with gusts of wind, gathering momentum until the silk broke apart or was slashed by flying debris. In one day, I noted at least five major destructions and rebuilds.

The spider didn’t hide under a leaf and wait for the foul weather to pass. It didn’t crawl around the corner to a more sheltered area. Perhaps its programming does not include the luxury of foresight, hindsight, or the ability to consider its options. Perhaps it thought the wind would never subside, as all it knows is right now.

I know what that’s like.

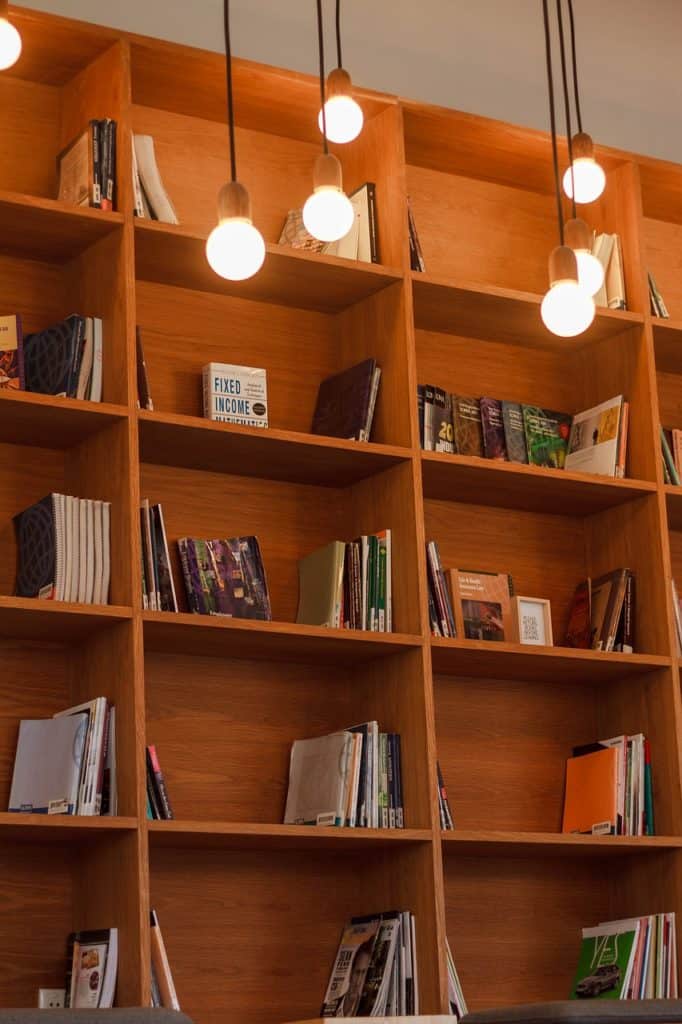

This weekend I made what appeared to be an impulsive purchase. I bought two bookshelves made from solid pine. Truthfully, it was a stretch on my budget and I itched to justify the expense to my partner, but refrained. He never asked, and this wasn’t an impulse. The bookshelves are vital to the foundation and stability of my house.

When I was a child in the early ‘70s, my father spent the bulk of one winter building an entire wall of bookshelves set upon a cabinet. His work, while not particularly artistic, was precise. He routed the cabinet doors to match the style of the original cabinetry in the house, and stained the wood a light walnut. When the project was finished, he placed the television on the cabinet top, loaded his stereo equipment and records into the cabinet, and wired the speakers that sat ceiling high on each side of the wall. The rest of the shelves were filled with books. Thin white spines of a dozen or so volumes of American Heritage took center stage. The smaller shelves were lined with engineering texts, atlases, encyclopedias and dictionaries.

My father did not indulge in fiction or the occult but my mother did. She had a few shelves of her own. I distinctly remember her pulling Linda Goodman’s Sun Signs from the shelf on a few occasions. How does a Scorpio woman married to a Sagittarius man, with a Gemini daughter and Taurus son, manage to stay healthy and sane? I imagine her licking her index finger to turn the page. Answer in retrospect: she doesn’t.

I have wondered if either of my parents acknowledged, or even recognized the sentiment behind this grand woodworking project. Maybe it was as straightforward as it seemed, my father wanted some more bookshelves so he built them. But considering all of what it took, there appeared to be some other motivation, even if it were subconscious. He had little experience with woodworking, and none of the tools. He had to buy the tools and learn how to use them. This project required investment, determination and courage. Courage, because my mother’s father was a professional cabinet maker of some renown. He was also a cold, materialistic man who never gave a damn about his daughter.

Unfortunately, that bookcase would provide the backdrop for some tragic performances. My family fought dramatically. The shelves held themselves and all of their content, despite the slamming doors and flying house plants. They never dropped a book or allowed one to lean in the turbulence. They stood neutral to a domestic war, wise soldiers, plank to paper. The shelves held the books, but they could not hold on to us.

My parents eventually divorced. My father kept the house while my mother, brother and I moved into an apartment. The bookcase developed dark gaps, like missing teeth, with the result of property division. I visited frequently, then moved back in with him a year later. My presence did nothing to ease his fury or my despair. We both sunk like chainless anchors. My father wandered the sparsely furnished house with a can of beer in his hand, and began using the living room like a garage. He often went out to the local singles bar. When he was home, I hid in my bedroom, empty but for a twin bed and night stand. He hated eating alone and pleaded for me to join him, but I hated eating and refused his food. When he wasn’t home, I leaned my head against one end of his bookcase and cried.

My parents eventually divorced. My father kept the house while my mother, brother and I moved into an apartment. The bookcase developed dark gaps, like missing teeth, with the result of property division. I visited frequently, then moved back in with him a year later. My presence did nothing to ease his fury or my despair. We both sunk like chainless anchors. My father wandered the sparsely furnished house with a can of beer in his hand, and began using the living room like a garage. He often went out to the local singles bar. When he was home, I hid in my bedroom, empty but for a twin bed and night stand. He hated eating alone and pleaded for me to join him, but I hated eating and refused his food. When he wasn’t home, I leaned my head against one end of his bookcase and cried.

A deep gash developed along the midsection of my family and soon we were watching each other bleed. My brother worked up a rap sheet. My father’s stomach tried to digest itself. Between my 23rd birthday and her 45th, my mother had a stroke that instantly killed her. I withdrew, then wandered away.

I often walked the neighborhood of my rental at dusk. With hands in my pockets, I waited for that brief but magical moment when people turned their lights on indoors before closing the blinds. It called to mind a line from a poem written by a Turkish poet, Nazim Hikmet: “ Bir pencere sarı sıcak…,” “A window, yellow and warm…” He had been exiled to Siberia and deeply missed his wife and country. Walking through heavy snow at night he saw a lit window through the Beech trees. He imagined the occupants calling out to him, inviting him inside. The poem is called “ Karlı Kayın Ormanında.”

Although forcibly separated, Hikmet had a family and a home. Mine got lost. I imagined knocking on the door of one of the houses I passed on my walk. The family would welcome me with a warm and genuine embrace. While they cheerfully bantered in the kitchen together, I would pull the blinds down in all the windows. Then I would select a book from the shelves, settle in a chair and immerse myself within the family’s acceptance of me, a part of their whole.

I tried to create a home for myself. I bought three bookshelves from K-mart. They were each 6’ high, made of particle board and walnut laminate, assembly required. I dedicated my expendable income to filling those shelves with literature, albeit in paperback. When I had on rare occasions a visitor, they would ask incredulously, “Have you read all of those books?” I beamed. “Yes. Yes, I have.”

I moved those cases and even more books into a marriage. He was bright and solid, with a promising career in aerospace engineering. If he were a rock, I was the wind and nothing he designed could fly with me. An unwise pairing from the start, our wedding guests were hedging bets, I suspect. I was the one to bring Anne Sexton along for our honeymoon. He just brought his swimming trunks. It wasn’t long before I packed my books and left.

I found a one room efficiency to rent and used the bookcases as a divider, sheltering my bed with their backs. I turned the black cardboard backing into a canvas. With glow in the dark paint I drew the moon and the stars, and a gentle Goddess to govern them. Then I sold the bookcases and most of my books, so that I could leave the state unencumbered.

Since the age of 14, I have moved house roughly every two years of my life. My time alone has always been a rebuild, like the spider repairing its web between gusts of wind. I continuously mended a weakly anchored life in preparation, and with the expectation, that it would be punctured by brief and destructive relationships. I drifted on threads composed of one part hope, three parts despair. Against all odds, I recently managed to buy my own house. I moved in a month before I turned 50. I share it with my partner who does not care about books or the shelves they sit upon. He is not a curious man. We dated briefly when we were teenagers, then thirty years passed without contact. Now we grant each other structure where we need it, and freedom where we don’t. It works, this relationship, despite – or more likely because – it rests on the implicit agreement that this house is mine.

I did some investigation into the life cycle of the Spiny Orb Weaver. They are common throughout the south, and live for less than a year. The male, in search of a mate, will approach a female’s web and tap in four beat measures. If the vibe feels right to her, she’ll respond and together they’ll seal their fate. The male will die a few days afterward, still hanging from her web. The female will follow once a sac of fertilized eggs has been secured. There is humor here, as dark as only nature can conceive. The punchline surpasses nature’s penchant for lethal sex. I can hear the echo of that epic snicker encoded in my own DNA.

I have reserved a shelf on one of the new bookcases for photographs. There is one of my father and me on his sailboat, taken shortly after my divorce. I am smiling, but he isn’t. My mother, framed in scratched up brass, shows off a bouquet of flowers she’d just received. There is my brother towering over me, his arm awkwardly hanging around my neck. I write this without looking at the photographs, then I look at them and realize my descriptions are not exactly accurate. My father is smiling, slightly. My brother has his hands clasped together at his hips and my arms are crossed. My mother is as I remembered.

I grapple with mortality, theirs and mine. I am not sure which is more difficult, to lose or to be lost. I step outside to check on the spider. She is still there, resting in the center of her web. It is intact with a dead fly in the weave. No one has come to call on her, yet. I briefly consider killing her. I reconsider, and take her picture.

About the Author – Amanda Bloodgood

About the Author – Amanda Bloodgood

Amanda Bloodgood lives in Hampton, Virginia, with her partner and two cats. She owns a small housekeeping business and writes when no one is looking.

Did you like this non-fiction story by Amanda Bloodgood? Then you might also like:

The Red Jeep

No Pain, No Gain

Gelato and Frost

Recipe for Saying Goodbye

Cookies for Breakfast

2024 Micro Nonfiction Story Writing Contest Results

Congratulations to the winners of the 2024 Dreamers Micro Nonfiction Story Writing Contest, for nonfiction stories between 100-300 words.

2024 Place and Home Contest Results

Congratulations to the winners of the Dreamers 2024 Place and Home Contest, based on the theme of migration, place & home.