Dance While the Music Plays

– Nonfiction by Conor Hogan –

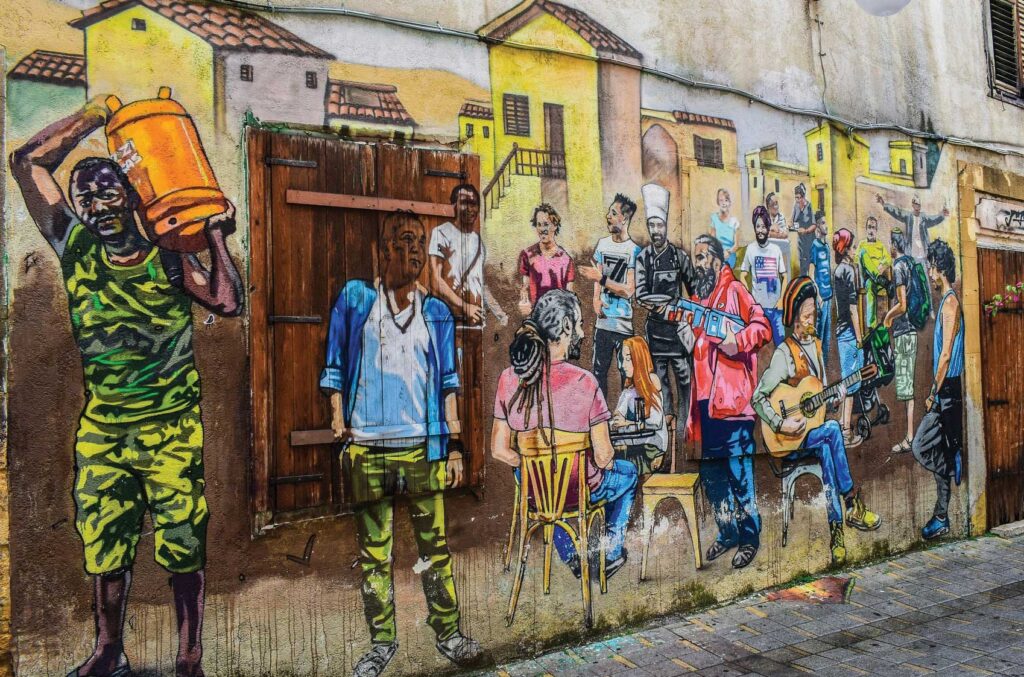

After my first day volunteering at the Kino Border Initiative in Nogales, Sonora, everyone stayed late to celebrate the birthday of Esteban*, a man who was sleeping at the shelter. Luisa, a woman who owned a bakery in Chilpancingo before violence forced her to flee, baked an enormous tres leches cake, and we all sang las Mañanitas. Once everyone ate their fill, people cleared the tables from the middle of the cafeteria and Luis, Esteban’s brother, plugged his phone into a shoebox-sized speaker. Payaso del Rodeo’s unmistakable opening riff filled the cafeteria, and people scrambled into formation with cheers. Soon, migrants and volunteers alike were line-dancing and twirling invisible lassos as Eduardo Gameros sang: “Cruzando la frontera, me encontré con él.”

As I tripped over my feet trying to keep up with the accelerating steps, I felt confused. I’d taught in central Mexico for two years, and heard plenty of horror stories about the border from my students. Many had moved to escape the brutality of the cartels in the north. They’d told me about the bodies swinging from bridges in Juárez and the mass graves unearthed outside Tijuana. Meanwhile, for my friends and family in the United States, the situation at the border was either the starkest metaphor for a national purity under assault, or another egregious example of state-sponsored sadism. Either way, it was understood as a place of horrors. Yet here I was, a quarter mile south of the wall, and everyone was laughing and dancing. Huh, I thought. What gives?

We who have witnessed the rise of illiberal nationalism in our societies know this mobbish glee masks a profound weakness. We all now live with the unease that accompanies any failure to rise to a critical moment. We all feel the exhaustion of constant ethical contortions, as we try to jam the latest disgrace into some frame of normalcy. It is far past time for those of us living in these rich countries to confront the gross injustices committed along our borders, in our name, against some of the most vulnerable people on the planet. Not just for their sake, but for our own.

The last two decades exposed the delusion of the neoliberal dream: that subordinating everything to the frictionless movement of capital would end history. That Reaganomics would produce a global coalition of liberalized democracies, everyone’s standard of living steadily rising on the tides of free trade and small government. But instead, wealth concentrated in the coffers of a few billionaires, while purchasing power for the median Westerner stagnated or declined. The carbon in our atmosphere transformed from theory to fact, fanning wildfires and whipping up hurricanes of unprecedented magnitude. The U.S. dragged its allies into a disastrous, protracted war in the Middle East. Rather than respond with a turn toward pro-social, ecologically responsible political movements, however, many embraced vitriolic authoritarians, who blamed our problems on the easiest scapegoat available: the immigrant.

In the United States, when an infamous megalomaniac rode a golden escalator to a podium and announced that those crossing America’s southern border were criminals and rapists, most progressives dismissed him. We assumed the age-old trick of robber barons leveraging racial grievance to distract from their thieving had run its course. That Donald Trump’s corruption was so obvious, no one would buy his shtick. We kept arguing about which strands of the social safety net to strengthen, certain that the MAGA movement would soon collapse beneath the weight of its leader’s countless lies. We underestimated the appetite for a simple enemy, and a simple solution: the reason that you are struggling to make ends meet is not because the ultra-wealthy have lobbied to keep wages depressed and tax loopholes gaping. It’s because there are evil foreigners invading to the south. Therefore, we should build a wall.

The quadrennial that began on January 20th, 2017, saw the degradation of many institutions by the President of the United States: personal attacks against U.S. judges, false claims that the American election system was rife with fraud, and the constant vilification of the media. But nothing was more debased than the United States’ border with Mexico during the four years Donald Trump was in power. Already riven with policies both inhumane and remarkably stupid, the border became the best representation for the incompetent malice that characterized Trump’s entire administration.

Caitlin Dickerson, in an investigation for The Atlantic, explains how prior to 9/11, America’s Border Patrol was a cursory, ineffectual agency. People crossed the border to work, to visit family, and to buy goods on one side or the other. But after the attack on the Twin Towers, “the Border Patrol Academy transformed from a classroom-like setting, with courses on immigration law and Spanish, into a paramilitary-style bootcamp…No longer content to police the national boundary by focusing on the highest-priority offenses, the Border Patrol now sought to secure it completely. A single illegal border crossing was one too many. The new goal was zero tolerance.”

In The Line Becomes a River, a memoir recounting his time as a Border Patrol agent, Francisco Cantú sketches the violence that this avowed intolerance enacts upon the psyche of the continent. Cantú repeatedly poses the same question in different forms: what does the modern proclivity, for transmuting individual pain into mild statistics, do to us? Cantú recalls the teenagers he found dead in the desert and the men he arrested who spent days drinking their own urine. He describes the cartels who have gotten rich since 9/11, unspeakably savage organizations who last year earned 13 billion dollars trafficking migrants: “As border crossing became more difficult, traffickers increased their smuggling fees. In turn, as smuggling became more profitable, it was increasingly consolidated under the regional operations of the drug cartels.” Cantú explains how “coyotes,” after shepherding migrants into the U.S., often pack them into drophouses in cities like Phoenix, then call their families and torture them over the phone until a relative pays ransom. This is what we in North America have decided is preferable to a functional immigration process.

Predictably, as official policy strengthens cartels, the law enforcement agencies whose officers are charged with fighting them adopt increasingly vicious tactics. Cantú remembers a lawyer telling him about a CBP agent he represented who “was framed by his own colleagues in the patrol because…he showed too much compassion in the line of duty…He carried an injured woman on his back through the desert and the other agents started thinking he was soft…so they set the guy up. They made it look like he had beaten someone up in the field…the Border Patrol, the marshals, it’s like they forget about kindness. I’ve almost never seen these guys express any humanity, any emotion…How do you come home to your kids at night when you spend your day treating other humans like dogs?”

This conversation happened years before the Trump administration’s Family Separation Policy, which went into effect in May of 2018. Before, as Dickerson writes, “companies eagerly accepted multimillion-dollar government contracts, housing children in huge facilities such as a former Walmart, which was at one point used to detain more than 1,000 children.” Before Border Patrol agents began ripping toddlers from their parents’ arms, deporting mothers to Honduras and shipping their children to HHS offices in Chicago, with no plan to ever reunite them. Before President Biden put immigration reform on a backburner, cowed by how his conservative colleagues might frame any change in posture towards people migrating in search of a better life.

If we’ve learned anything from the past half-century, we should have learned that punitory approaches to problems invariably exacerbate the issue they are supposedly meant to solve. The War on Drugs, Operation Iraqi Freedom, Border Patrol’s Zero Tolerance policy: they have all enriched a handful of grifters (private prison owners, international arms dealers, the “capos” of the Sinaloa cartel) and immiserated millions. Meanwhile, the reasons for dramatically increasing immigration into countries like the United States and Canada are manifold, and indisputable. With our declining birth rates, with our vast swaths of sparsely populated land, with baby-boomers entering old age and not enough caretakers to assist them, encouraging immigration is the single best thing we could do to increase our continent’s prosperity.

Studies repeatedly demonstrate how immigrants, both skilled and unskilled, are a net boon to everyone’s wage and standard of living. In Canada, immigrants own a third of small businesses with paid employees, while in the United States, immigrants are disproportionately represented among Nobel Prize winners. Particularly if North America hopes to have any bargaining power with China in the upcoming decades, expanding our population is a patently obvious first step. However, as Matthew Yglesias writes in One Billion Americans, “…some people just plain don’t like foreigners and don’t want them to come here and are indifferent to the basic facts about economics and the logic of international power.” The fact that this xenophobic political faction continues to dictate our inhumane, self-destructive immigration policies should spur the rest of us into action. Why doesn’t it?

According to the UN’s most recent data, by the end of 2021, one in 88 people around the world had been forcibly displaced from their homes. Fleeing poverty, violence, or natural disasters, most took refuge in neighboring low- or middle-income countries. Those who made it to the borders of rich countries, however, were usually told they were not welcome. They were informed that the people living inside these rich countries did not want them and would not help them. That, in fact, the most energetic political movements in many of these rich countries were characterized by gleeful crowds chanting about keeping them out.

The Kino Border Initiative is run by a mix of lay people, Jesuits, and Missionary Sisters of the Eucharist. They provide material, psychological, and legal support to migrants, advocate for policy change, and offer immersion opportunities for students to learn about the realities of the border. The KBI is also a paragon of strength and effectiveness in the realm of humanitarian aid. I have volunteered for NGOs in Argentina, Guatemala, El Salvador, Mexico, and the United States. I also work as a smokejumper, a firefighter who parachutes into mountains to suppress remote wildfires. There is usually a marked cultural difference between the places I have volunteered, and that of a fire camp. The world of wildfire response is defined by strict chains of command, a high tolerance for risk, and an inclination toward taking aggressive action. The people I’ve met volunteering, on the other hand, are often better at writing eloquent mission statements than building the systems necessary for putting their mission into practice. These nonprofits are often hampered by confusion, full of people unsure about their assignments and leaders so worried about offending their subordinates that they don’t tell anyone what to do.

This is an Achilles’ heel for many social justice organizations: the aesthetic of equity and inclusion can hinder efficiency. Meanwhile, it turns out that the same personalities who prefer impermeable borders, harsh legal systems, and demagogic strongmen also excel at the administrative tasks necessary for yielding results. This is why hyper-organized institutions like the military and police are associated with right-wing governments, and why so many firefighters lean conservative. Political psychology studies demonstrate how progressive people are characterized by openness (receptivity to new ideas and new experiences), and conservatives by conscientiousness (the quality of wishing to do one’s work well and thoroughly). While openness is vital in academia and the arts, in the trenches of emergency response, conscientiousness is much more valuable. What is happening at the U.S./Mexican border is an emergency. There are people trying to escape the pandillas terrorizing El Salvador, the mass starvation occurring in Venezuela, and the horrifying collapse of Haiti. Cartels have imposed sophisticated, violently enforced systems of exploitation that ensnare these refugees after they are turned away by stone-faced Border Patrol agents. The scale of human suffering created along this imaginary fault line is akin to an unceasing, major earthquake, and the work of ameliorating this suffering has been left almost entirely to NGOs like the KBI. When I arrived in Nogales, I expected to step into the muddle that often typifies nonprofit disaster relief.

Instead, it felt like I was checking into the Incident Command Post of a large wildfire. Victor Yanez, the KBI’s Director of Migrant Services, gave me a thorough in-briefing on how different sectors of the Kino work, walking me through detailed flow charts and contingency plans for various scenarios. The KBI’s philosophy of “holistic accompaniment” could connote some airy, bohemian idea, a phrase you might hear at a yoga retreat in Bali. However, in the context of serving migrants, holistic accompaniment means figuring out how to provide food, clothing, temporary housing, counseling, and legal assistance to the throngs of people who arrive at the Kino’s front door every day. Caring for the whole person, it turns out, requires serious tactical prowess.

Like everything about the far right, the anti-immigration movement is characterized by fear. Mark Hetherington and Jonathon Weiler explain in their book Prius or Pickup: “Fear is perhaps our most primal instinct, after all, so it’s only logical that people’s level of fearfulness informs their outlook on life. If you perceive the world as more dangerous, then…you’re more likely to prefer to drive a big, sturdy vehicle, have a large, obedient dog for a pet, and vote Republican…If you see the world as less perilous, you feel [free]…to work harder to understand the perspectives of people who are different from you.”

As the right radicalizes, it turns to more cartoonish symbols of power to compensate for their fear of the world. Thus, we have rising reactionary star Ron DeSantis releasing cringe-worthy Top Gun campaign ads, Donald Trump tweeting memes of his own face superimposed atop Rocky Balboa’s body, and frenzied crowds screaming: “Build the wall! Build the wall!” In a political marketplace that rewards the extreme, a fear-based rhetoric will quickly devolve into infantile notions of good guys and bad guys and seek a frightened child’s solutions. But while hiding from boogeymen in a pillow fortress might have worked in kindergarten, out here in the real world, we must act like adults. Recently, the far-right has turned once again to a language of attack to describe the people arriving at America’s southern border. “Greatest crime ever committed against the United States, by far. Nothing has ever come close to what we’re seeing now,” Tucker Carlson blubbered on his November 3rd, 2022, show when describing footage of people walking into Texas. Trump, in a speech announcing his candidacy for the 2024 presidential race, said: “Our southern border has been erased and our country is being invaded by millions and millions of unknown people, many of whom are entering for a very bad and sinister reason.”

A frustrating aspect of our societal conversation is how readily people accept the far-right’s notions of fortitude. Nationalist movements shroud themselves in an iconography of weapons, vulgarity, and rage, and many think, that is strength. Despite threatening to torture dissidents, they say, at least Jair Bolsonaro is aggressive. Despite his flirtations with eugenics, at least Viktor Orbán is forceful. Despite his observable sociopathy, at least Donald Trump is assertive. At least they “speak truth to power,” from their presidential mansions. Where Martin Luther King and Cesar Chavez once represented the counterculture, now bigots like Nick Fuentes and Stefan Molyneux have managed to convince many young people that it’s cooler to rebel against imaginary Marxist professors than government brutality. Meanwhile, the caricature of the “social justice warrior” implies some frail hipster wailing about microaggressions between sips of their lavender kombucha.

This is exactly backwards. Who more embodies courage: Maxime Bernier, frothing about the way immigrants “destroy social cohesion,” or the KBI’s Sister María Engracia Robles Robles, who has served refugees in Nogales since 2007? Who is stronger: Tom Homan, the American Immigration and Customs Enforcement director who came up with the idea to separate children from their mothers, or the thousands of Venezuelans who’ve walked across the Darién Gap, one of the most dangerous stretches of land in the world? When did we agree that lobbying for state abuse was punk-rock, and that standing in solidarity with the oppressed lame?

I spend my summers jumping out of airplanes and flying parachutes into the mountains. From May to October, I work 16-hour shifts digging fire-line or running a chainsaw, trying to catch wildfires before they explode. The work pales in comparison to what the staff at the Kino does every day. For the past month, in between serving food and handing out clothes, I’ve helped conduct intake interviews with migrants arriving at the KBI. I’ve listened to a mother from Michoacán calmly discuss how the mafia promised to murder her children if she didn’t pay their cartel tax. I’ve handed freshly deported teenagers sweatshirts after the Border Patrol released them in the middle of the night and refused to return any of their belongings. I’ve had to explain to victims of torture that the United States has not accepted asylees for over two and a half years. I’ve felt angry and ashamed, all-too familiar sensations for any gringo living in Latin America.

But I’ve also felt an unfamiliar hope. Every morning, Claude, a man from Haiti, greets me with a big smile and a fist bump, and catches me up on the latest drama in international soccer. I spend the first few hours of my day sorting clothes alongside Vicki, a woman who fled Guerrero, the two of us bantering about the superiority of our respective folding techniques. I eat lunch with Diego, a political refugee from Caracas, and occasionally watch him get choked up as he remembers another indignity he endured on his journey north: robbed in Ecuador, extorted in Chiapas, waving goodbye to his boyfriend through bullet-proof glass in Arizona. I watch him smile self-deprecatingly and thumb his eyes, then look around the cafeteria and exhale. “This is the only place where they listened,” Diego often says, and shakes his head.

After a month of volunteering at the KBI, a question inevitably arises: why is this place so unique? Because the environment at the Kino is special, but it need not be. It is simply a place where the needs of the vulnerable are taken seriously. A place where people help other people, instead of exploiting them. The reason migrants walk through the Kino’s cafeteria as though they’ve just set down a hundred-pound backpack is because the weight of dehumanization is exhausting. The reason that the people who work at the KBI can sustain their Herculean effort is because a sense of common, noble struggle is the most invigorating sensation a person can experience.

Much has been said about the crisis of meaning infecting Western societies. Why is it that the richest countries in the world also have such high rates of anxiety, depression, and drug overdoses? Why do we see membership in extremist groups skyrocketing? What are people really searching for when they swallow a hydrocodone or join a neo-Nazi group? Is there something wrong with the structure of modern life?

A common symptom of living inside bureaucracies, of spending hours of our day online and viewing each other through a matrix of adjectives, is a sense of apathetic futility. Faced with the tidal roar of the world’s injustice, we assume our own impotence, and carry on with our lives. We rationalize the decision, again and again, to choose money over people, to choose convenience over engagement. Any donation we do give, any afternoon we spend at a soup kitchen or homeless shelter, is felt as penance, as an attempt to ward off our vague, omnipresent guilt. In a culture that positions the accrual of wealth as the sole end worth pursuing, time spent serving the marginalized can only be understood as time wasted.

There is a parable that reappears every now and then in books and commencement speeches: A man is walking along a beach, where thousands of starfish have washed ashore. The man comes across a boy, who is picking up starfish one by one and hurling them back into the sea. The man asks the boy, What are you doing? and the boy replies, I’m throwing them back; otherwise, they’ll die. The man gestures up and down the sand, at all the starfish asphyxiating in the morning sun. Look around, says the man with a condescending smile. You can’t possibly make a difference. The boy picks up a starfish and tosses it into the waves, then turns to the man and says, Made a difference to that one.

It’s a good parable. However, every version I’ve read omits the most important part of the story: the difference it makes to the boy. As the world complexifies, we assume the solutions to any problem must be equally complex, and thus, beyond our realm of possible action. Why feed one hungry person, when whole nations are starving? Why give one child clothing, when millions are shivering? Why not accept our powerlessness to improve the world, and focus instead on increasing our own material comfort?

This is the fundamental challenge of modernity: to practice decency within the confines of a single, morally compromised existence. Never have we been so aware of humanity’s collective iniquities, or of our own smallness. Notifications constantly interrupt our days to show us injustices occurring around the globe, injustices we tacitly support. They offer glimpses into a cacophony of lives unfolding unrelated to our own and remind us that the world will not notice our absence. Our technology trains us to think in this meta-rational manner, where any decision simultaneously appears insignificant and unethical. Driving to work, eating a sandwich, buying a pair of headphones: we can be certain that these quotidian decisions contribute to some unfairness, somewhere.

A noxious political culture has erupted in response to this cognitive challenge confronting each of us: because trying to help the most vulnerable members of our societies is difficult, ambiguous work, do not try. Instead, focus on how your own life is less-than-satisfactory. Trumpet about the ways you’ve been wronged and mock anyone involved in a project of ameliorating the world’s suffering. Call them naive, question their motives, accuse them of virtue-signaling. The rising popularity of authoritarianism, more than anything, symbolizes capitulation. Turning to rightwing extremism is characterized by the same cheap thrill we feel the moment we decide to quit exercising, or to eat fast food, or to binge on our substance of choice. The moment we decide to stop striving, and instead surrender to our base impulses. Our climbing rates of depression and loneliness represent the hangover such a decision produces. Meanwhile, if there is any universal truth in this life, it is that collective struggle, in service of some greater good, is the most reliable path to meaning. To an existence that justifies itself completely. Those who work at the KBI know this, and the joy that radiates through their building serves as proof. There are opportunists trying to trick us into thinking that walls make us mighty and that solidarity should be derided, because their privilege depends on our atomization. They are liars. It is within our power to laugh and dance and work together to build a more just, beautiful world, and the decision to participate is an endless source of strength. The poet Mary Oliver once wrote:

“…as the times implore our true involvement,

The blades of every crisis point the way.

I would it were not so, but so it is.

Who ever made music of a mild day?”

There is music playing, in the most unexpected places. We just have to go, and listen.

*Some names have been changed to protect privacy.

About the Author – Conor Hogan

Conor Hogan has been a firefighter with the US Forest Service for eight years. He graduated from the University of Montana Honors College with a degree in English and Spanish, and then spent two years in Mexico on a Fulbright scholarship. His writing has been published or is forthcoming in Overtime, Anglica: An International Journal of English Studies, and The Hamilton Stone Review, among others. He currently works as a smokejumper in Washington state.

Did you like this story by Conor Hogan? To see more like it, checkout our Nonfiction category.

Like reading print publications? Consider subscribing to the Dreamers Magazine!

2024 Micro Nonfiction Story Writing Contest Results

Congratulations to the winners of the 2024 Dreamers Micro Nonfiction Story Writing Contest, for nonfiction stories between 100-300 words.

2024 Place and Home Contest Results

Congratulations to the winners of the Dreamers 2024 Place and Home Contest, based on the theme of migration, place & home.