Integrative Ancestors, redux: A Child’s Story from the past to the future

– By Gregory Stephens – October 2, 2018

Fall 2018

When my daughter Sela was three, she invented a story about Bob Marley and Frederick Douglass. I put her allegory in the “Afterthoughts” of On Racial Frontiers: The New Culture of Frederick Douglass, Ralph Ellison, and Bob Marley, published by Cambridge University Press in 1999. I would travel all over the U.S. and to England and Wales, giving lectures and radio interviews, from the BBC in London, and “To the Best of Our Knowledge” in Madison, Wisconsin, to “Forum” on KQED in San Francisco.

That was my public face during those years, a would-be interracial mediator. But if you look at the video of my lecture at the San Francisco Public Library on February 22, 2000, near the end you’ll see Sela, age five, coming on stage to tell her story, in both English and Spanish. In the Q&A you can also see an African American gentleman expressing a barely controlled outrage and contempt for what he saw as a “white man” encroaching on his cultural territory.

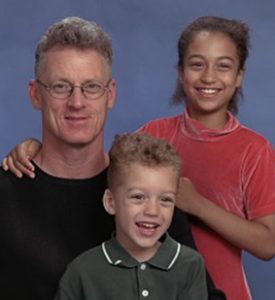

Beneath this public story is a private drama, which is my effort to find broader meaning in the familial and interracial ruptures which I experienced. In the family photos I have from the time when I was writing and publicizing On Racial Frontiers, there is no woman present. This photo was taken in Oklahoma City, around the time when I went through a divorce and then gained custody of Sela and Samuel, about six and two years old here, respectively.

Beneath this public story is a private drama, which is my effort to find broader meaning in the familial and interracial ruptures which I experienced. In the family photos I have from the time when I was writing and publicizing On Racial Frontiers, there is no woman present. This photo was taken in Oklahoma City, around the time when I went through a divorce and then gained custody of Sela and Samuel, about six and two years old here, respectively.

While writing the book, I had an epiphany that I was trying to communicate with my estranged wife, an African American woman who had intensely racialized our relationship. A broader audience was people who lived “on racial frontiers,” by which I meant the millions who in their everyday lives lived and loved and worked professionally in inter-racial contexts, most often routinely. That was an invisible norm hidden by overheated rhetoric, especially about black victimization and white guilt, i.e., the “white liberal guilt complex.”

But at every point, as I conceived of, researched, wrote, and publicized On Racial Frontiers, I also thought of a third audience, which was my children, and other “mixies” in their generation. I wanted to provide a map of where they came from, along with a sense of better options for the path down which they were headed.

Sela seems to have intuited all of this at a very young age, and came up with the story about Marley and Douglass which is at the heart of my present reframed “Afterthoughts.”

Here’s the way I pitched the book to a general public, in language that made its way onto the Amazon page, and other public forums:

Douglass, Ellison and Marley lived on racial frontiers. Their interactions with mixed audiences made them key figures in an interracial consciousness and culture, integrative ancestors who can be claimed by more than one group. An abolitionist who criticized black racialism; the author of Invisible Man, a landmark of modernity and black literature; and a musician whose allegiance was to “God’s side, who cause me to come from black and white.” The lives of these three men illustrate how our notions of “race” have been constructed out of a repression of the interracial.

In the “Afterthoughts” at the end of On Racial Frontiers, I challenged readers to “shift gears” while I adopted “a more personal voice.” Addressing the reader directly, I wrote:

I ask you to think along with me for a few pages without footnotes, in a more reflective mode, about how the issues that have been raised here might appear to a reader (or a nonreader) of a future generation.

Writing those lines in 1998, I was 10 years removed from a career as an award-winning songwriter in Austin, Texas. During the 1990s I published cultural criticism and political commentary in the San Francisco Chronicle, through syndication with the Pacific News Service, etc. I continued to do radio “edutainment specials” with my friend DJ-RJ in Austin. All of those elements of my writerly voice no doubt led some scholars to view this book as an “impassioned… and lyrical meditation.”

However, it was fatherhood, above all, that drove the scholarship, and directly shaped these “Afterthoughts.” My daughter Sela arrived in 1994, and my son Samuel was born in mid-1998. In trying to imagine how future generations might access my story (about interracial culture), I was conscious that they might be “nonreaders,” and that scholarship would likely be an inadequate way to reach a generation raised on social media, and attuned to visual narrative.

The matrix for this reflection came out of children’s literature. Sela and I borrowed a stack of books weekly from the Berkeley library. Most of these books were bilingual (Spanish-English), or in Spanish. The context in which Sela told her story which I tried to memorialize is that I was parenting biracial children in Spanish. Their mother did not speak Spanish, while I had come of age in the Southwest, and had travelled extensively in Mexico and Guatemala. In some sense I saw Spanish as offering a route beyond binary racial conceptions of identity and community. In cultural terms, the often remarkable artwork of children’s literature was a part of our everyday lives, and certainly fertilized all of our imaginations.

Sela is a young woman now, and Samuel turned twenty in 2018. Readers (or nonreaders) can now formulate their own answers to my questions. I am sending this “message in a bottle” back out to the world, this time in a literary nonfiction wrapping. I have made only minor edits, because I feel that the questions posed to future generations, and the “child’s-eye-view” which animates and frames those questions, continue to resonate.

1998-1999 – “Afterthoughts”

A rhetorical question has guided this project. If educators and political leaders treated figures such as Frederick Douglass, Ralph Ellison, and Bob Marley as “integrative ancestors” who could be “claimed” by members of several ethno-racial groups, would this help us to envision how commonality and difference could coexist? Could such “integrative ancestors” give us some of the tools we need to construct a “multiracial democracy,” or to see ourselves as co-creators of a “new culture” which was moving beyond the language of race?

Having long contemplated variants of these questions, I have grown suspicious of sweeping generalizations. In a sense, my conclusions are inherent in the details of this “map.” It is a way of seeing that I have suggested: a corrective to a blindness regarding our previously repressed or denied interracial heritage. Whether the reader finds that this perspective is recovered vision, or just projected desire, to a degree is in the details of the map itself.

This project requires an effort at mutual imagining. So I am at the mercy of the reader: the degree to which he or she finds my account persuasive depends, first, on whether it has resonance in his or her own life experiences. And beyond that, whether or not my version of our-story rings true also depends on the reader’s relative willingness to take a “leap of faith”—to look at the world, at least briefly, without the blinders of racial mythology. In the final analysis, this involves an issue of trust: the reader must find the author a relatively trustworthy observer, to be able to look beyond the messenger to the message.

I remain convinced that these big questions are worth asking: “how do we build a multi-racial democracy?” Or, “what kind of language do we need to build multi-ethnic coalitions?” And, “what cultural resources can we give our children to prepare them for the future?”

We don’t have a blueprint for these challenges. But the questions themselves serve as a horizon towards which we can orient ourselves. Douglass, Ellison, and Marley all believed that it was impossible to prepare for the future without having a thorough knowledge of the past. I obviously agree. Yet I adhere to a sort of motto: don’t forget your history, but don’t get stuck in the rear-view mirror.

It is humbling to realize that the very language we choose to discuss the problems of the present may prevent us from communicating with those of the future who—truth be told—would probably value a bit more clear thinking on our part, about how we created the various crises we have left them to face. The crisis of “race” is just one of these messes. In the long run, I have to think that it really is a decoy.

I began writing the first version of On Racial Frontiers shortly after my first child, Sela, came into this world. And I am completing it as she turns four. During the various revisions, I have often wondered if it were possible to write in a fashion that Sela would be able to understand, after she entered college around 2012. This may be just “entertaining a fantasy”: engaging in contemporary theoretical or political debates, for instance, often requires a language that is incompatible with a college student of my own era, much less the future.

I still struggle with this idea. If I am writing about the history of a multiracial community, or an interracial culture, then I also ought to be trying to make visible the relevance of this “story” to the offspring and the inheritors of that community and culture.

The thought of writing something that would one day be of value to my children has not been entirely self-willed. Some of the “culture heroes” of this book are already a part of Sela’s imagination; she is already revising their stories, and asking for my feedback on these revisions.

I have had life-sized portraits of Douglass and Marley above my desk ever since Sela was born. I wanted her to grow up surrounded with images of people who look like her. I wanted her to see that her cultural heritage is shared by both her mother and father. By the time Sela was one, she was already speaking to these portraits, calling them “abuelo Fred” and “tio Bob,” just as with her child’s imagination, she spoke to other objects throughout the house—Mexican masks, pictures of her grandparents and cousins, etc.

I never explained to Sela anything about her “grandfather Frederick” or her “uncle Bob,” other than that I was writing a book about them. (Although we have danced to Marley’s music since she was an infant.) But around the time that she turned three, Sela suddenly “wrote” her own story about Douglass and Marley, which she has repeated to me many times. She began asking me, eventually, to repeat it back to her. Then she seemed to get the idea that this story existed somewhere outside of her: she would point to a book, and ask if her story about Bob and Frederick was in there. Finally, she asked me if I was going to put her story in my own book. I told her that I would. It actually seemed like a good way to think about what different roles these “integrative ancestors” might play for their descendants in the future. I recount this story first in the language Sela used, Spanish, and then translate it to English.

Sela’s Frederick Douglass and Bob Marley Story

Frederick Douglass y Bob Marley caminaban juntos en el camino. Frederick se convirtió en una estrella y Bob se transformó en un león. Un fantasma atacó a Frederick Douglass pero Bob Marley le salvó.

[Frederick Douglass and Bob Marley were walking down a path together. Frederick transformed into a star and Bob changed into a lion. A ghost or an evil spirit attacked Frederick Douglass, but Bob Marley came to his rescue.]

At first, as an adult, I wanted to know more. But when I asked Sela where the fantasma came from, she told me: “mi corazón no quiere hablar.” Literally: my heart doesn’t want to talk, which is what she tells me when she doesn’t want to analyze something.

Well, out of the mouths of babes come some amazing things.

There was no way that a three-year-old could have known that the North Star was the name of Douglass’ first paper. Nor could she have known about the great significance of the Lion of Judah in the music of Marley and the Rastas.

Sela most likely plucked these symbols, not from a collective unconscious, but from the cultural resources that her Mom and Dad put at her disposal. Sela’s favorite story during her third year was El Rey León, or, The Lion King, which we read countless times in Spanish, and watched on video in both Spanish and English.

In one scene, Simba, still a cub, asks his father Mufasa, the Lion King, if they would always be together. Mufasa says that one day he will have to die, but that he will live on in the stars, always there to guide him. After he has grown, Simba imagines that he sees Mufasa in the sky, and hears his father calling him to remember who he is—to accept his destiny.

Sela was full of questions about this scene, trying to comprehend the meaning of death. She seems to have come to understand my explanation that Mufasa lived inside of Simba, in his imagination, in his memory. She wanted to be constantly reassured that I also would always live inside of her. And she seemed to project these concerns into her little fable about the transformations of Frederick Douglass and Bob Marley.

One of Sela’s other favorite books during her third year was Follow the Drinking Gourd, by Jeanette Winter (Knopf, 1988). This being in English, she read it with her mother, in fact requested it so often that we eventually had to hide it. She also watched the video version narrated by Morgan Freeman, with music by Taj Mahal. This is a touching fable of the underground railroad, in which slaves are guided to freedom by the “drinking gourd”—the Big Dipper, whose cup points towards the North Star.

Teaching any child about the history of race relations is a daunting challenge. There are perhaps some unique dynamics for interracial families. My determination to present Douglass and Marley as “integrative ancestors” to Sela had consequences I had not anticipated. During Sela’s third year, she developed a deep interest in slavery, in variations of skin color, and in how skin color and slavery are connected.

As an abolitionist parable, the Drinking Gourd is a tale that I, an “Irish-American” parent, find easy to identify with. Most of the “white” characters are sympathetic. Center stage is shared by Peg Leg Joe, a carpenter who travels from plantation to plantation teaching slaves a “freedom song,” and by a family of escaping slaves. There are Quaker families who house the fleeing slaves, and a white boy who brings them food. Yet this is not what Sela fastened on. What fascinated and troubled her was the picture of a white overseer holding a whip, standing over slaves picking cotton.

“Do all white people whip dark people?” she wanted to know.

Sela’s library is filled with books about interracial families, “brown” families from Latin America, and varieties of skin color from the world over. But what drew her imagination, as she began to read stories about slavery, was an association of whiteness with cruelty. We bought her a “beginning biography,” Frederick Douglass: Freedom Fighter by Garland Nelson Jackson (1993). Again, there are positive images of interraciality here—white children helping young Fred learn to read. But after Sela heard a line about Captain Anthony punishing slaves, her questions were:

“Does Dad own slaves?”

And, “white people are bad, right mom?”

Sela’s images of white people as bad, I began to realize, came from many sources—from Pocahontas, for instance, which despite being a Disney film, has a strong anti-colonial message, and which made it clear that “white men are dangerous.” By contrast, contrary to conventional wisdom, I have found that it has been easy to give Sela a positive image of “black” and “brown” people.

The real problem continues to be with a white/nonwhite binary, which is so deeply embedded in the culture that I have found it impossible to escape. I can only try to ameliorate it: I can hold my hand to a piece of white paper, to demonstrate the difference between the color white, and our concept of “whiteness.” And I can show her the contrast between her mother’s skin, and the black couch, to illustrate the difference between the color black and “blackness.” By this means, I try to teach her that most if not all skin colors are really different shades of brown. And I hope that she will grow into an understanding of “the true interrelatedness of blackness and whiteness,” as Ellison wrote.

I think this story sheds light on my earlier question: what cultural resources can we give our children to prepare them for the future? For my academic peers, a Disney film would typically be criticized for perpetuating negative “mainstream” values, while the story of Douglass would generally be placed in a “black box,” as an example of resistance to this mainstream. But in my child’s imagination, Disney and Douglass are not so easily separated into a “center” and a “margin.” I think that the way in which Sela has fused themes from several sources shows that the world of a Disney cartoon and the backdrop of a deeper cultural history do not have to be mutually exclusive.

Sela’s story also says something about how differently the “integrative ancestors” I presented in On Racial Frontiers might speak to someone in the future. I feel certain that Douglass, Marley, and probably later Ralph Ellison, will continue to speak to Sela. But I have no idea what she will draw from them, what form her own vision will take.

Listening to Sela’s questions about slavery, and about white people, I found myself thinking about the balances involved in trying to teach this history. How do you teach a child about the injustices of slavery, without painting all whites as being guilty of the atrocities of this system, or portraying all backs as its victims? Is it possible to teach this history without forwarding the tendency to think in black and white, or divide the world between whites and “people of color?”

When I hear questions about slavery and its legacy, from my child, or my students, I have two thoughts. I think that it must be important to know that, at the height of slavery, only 10 percent of whites were slaveholders. And I simultaneously think of the voices of students I have heard at Berkeley, who said that they did not want some white teacher trying to tell them that things were really not so bad, after all. So, I know that there is no correct way of telling this integrative history. And I know that, in this era, it is usually not possible to separate the message from the messenger.

As both a parent and an educator, I am committed to synthesis, to striking a balance. As much as I want my children to know about slavery and racial discrimination, I feel it is equally important to let them know about resistance to race prejudice—and that people of all colors took part in this resistance. Surprising contradictions of the underground.

I don’t think the importance of either historical truth-telling, nor the importance of having positive models to emulate, can be overestimated. Another parent will want to focus on the brutality of slavery, and will not feel that it is important (or even possible) to give their children an image of whites other than “oppressor.” Many parents will not teach their children anything about slavery, or imperialism, whatsoever. What differences will this make in our respective children’s attitudes about “race,” and how they treat each other, when they later sit in the same classrooms, and compete for the same jobs? More big questions with no easy answers.

I have tried to present this map of the “new culture” of racial frontiers as one available worldview: not as the right choice, but an important perspective that I believe needs to be included in the mix. Both the “frightful wrongs” and the “great and beautiful things” that individuals and nations have done need to be remembered, Du Bois said. More simply, Bob Marley’s words always echo in my ears: “tell the children the truth.” Tell them the truth, “so far as the truth is ascertainable,” in the words of Du Bois.

Where “race” is concerned, I firmly believe that we need to give our children multiple perspectives, and then allow them to maintain multiple allegiances. We should give them the freedom to choose not to choose, should this be their choice. Such a freedom will require institutional recognition of multiracial formations.

By way of leave-taking, I would like to borrow Sela’s image of Frederick Douglass and Bob Marley walking down the road together, towards the future, I presume. They change form, reappearing in a new face or form. They sometimes suffer attacks, and help each other out in moments of crisis. At the crossroads, they encounter Ralph Ellison. Like old friends, the three of them pick up on an old conversation that has no end. We listen in from time to time, and on the lower frequencies, they still speak to you and me. They have become a part of we.

About the Author – Gregory Stephens

Gregory Stephens is (in 2018-19) on leave from the University of Puerto Rico-Mayagüez, where he is an Associate Professor of English. He teaches Creative Writing, literature, film, and seminars in Cultural Studies and Writing Studies. Before grad school Stephens was an award-winning songwriter in Austin, Texas. He is the author of On Racial Frontiers: The New Culture of Frederick Douglass, Ralph Ellison, and Bob Marley (Cambridge UP). Trilogies as Cultural Analysis: Literary Re-imaginings of Sea Crossings, Animals, and Fathering is published by Cambridge Scholars Press (2018). The monograph Three Birds Sing a New Song: A Puerto Rican trilogy about Dystopia, Precarity, and Resistance, which combines ethnography and literary nonfiction, is in production with Intermezzo.

is (in 2018-19) on leave from the University of Puerto Rico-Mayagüez, where he is an Associate Professor of English. He teaches Creative Writing, literature, film, and seminars in Cultural Studies and Writing Studies. Before grad school Stephens was an award-winning songwriter in Austin, Texas. He is the author of On Racial Frontiers: The New Culture of Frederick Douglass, Ralph Ellison, and Bob Marley (Cambridge UP). Trilogies as Cultural Analysis: Literary Re-imaginings of Sea Crossings, Animals, and Fathering is published by Cambridge Scholars Press (2018). The monograph Three Birds Sing a New Song: A Puerto Rican trilogy about Dystopia, Precarity, and Resistance, which combines ethnography and literary nonfiction, is in production with Intermezzo.

Did you like “Integrative Ancestors, redux: A Child’s Story from the past to the future” by Gregory Stephens? Then you might also like: “Discovering Creative-Relational Inquiry.” Or, check out the articles in the Arts Research International Journal, including “A Beat of Goodbye: An Autoethnographic Account of My Last Days with Grandma” by our own Editor-in-Chief.