The Miracle of Joey Ramone

– Non-Fiction by Lee Gabay –

After the unconventional release of their 2014 album, U2 received overwhelmingly negative feedback. One day in September, Apple users around the world awoke to discover that all eleven Songs of Innocence had been automatically downloaded onto their iTunes playlists. To many of its recipients, this bold form of sharing seemed like an invasive marketing stunt. Music critic Sasha Frere-Jones wrote, “Don’t shove your music into people’s homes. Lack of consent is not the future.” Newsweek’s Zach Schonfeld also didn’t appreciate the offering and fumed, “that this, of all U2 albums ever, has been masterminded onto the laptops of millions of law-abiding adults who never asked for it.” To reconcile with the public backlash, U2 did a live Facebook chat to address their detractors. “Oops,” lead singer Bono quipped. “I’m sorry about that. This beautiful idea… we kind of got carried away with it.”

Yet not all of the 500 million customers in more than 119 different countries were mad at the band. For Rachel Wright of Brownsville, Brooklyn, the massive Apple rollout achieved what was perhaps U2’s generous intent: she happily unwrapped this digital gift and listened to the music of U2 for the first time. Rachel was 17, being raised by her single mother in the New York City neighborhood most stricken by gun violence, poverty, and failing schools—a situation that manifested itself in a relationship dominated by a maternal monologue of fear. Rachel responded to her difficult surroundings and her mother’s doomsday parenting style by turning away from the outside world and retreating deep into herself. She painted, sketched, wrote stories and listened to music. When required to step out of her place of temporary solace, Rachel’s maladapted social mechanisms made her stand out. Her shyness was taken as anger and her inability to speak deemed confrontational, triggering hostility from others. These ingredients made her a challenge to teachers and a target for bullies. Hence, completing the school day was never a guarantee for Rachel.

After years of bouncing from school to school, Rachel ended up in my English classroom at Brooklyn Democracy Academy (BDA), a transfer high school in Brownsville. Many of our students have been previously incarcerated or homeless and many have experienced foster or group home care. In the case of Rachel Wright, her foundational and emotional unrest lead her to us. BDA is essentially a last chance high school for over-aged and under-credited students— those who have exhausted all other academic options.

Young Not Dumb

On the first day of school in September 2014, I asked my morning class to write down their three favorite songs. The answers lacked range and didn’t really stray from a particular genre—almost unanimously heavy on hip hop and rap, and completely devoid of artists popular before the current decade. All with the exception of Rachel Wright. On her list were: “The Miracle (Of Joey Ramone),” “Every Breaking Wave” and “California (There Is No End To Love)” —the first three tracks on U2’s Songs of Innocence. I tauntingly asked Rachel, “Did you get the free copy on your phone?” She mumbled, “yes.” I immediately began to sing the songs. After 20 years of teaching, I thought that I had finally found a student with whom I could obsess over my favorite band, U2. But I soon realized that this student didn’t talk.

Rachel was the first to arrive in the classroom each morning and first to leave when the bell rang. Her written work was energetic, sophisticated and always complete. When the class read Claude Brown’s Manchild in the Promised Land, Rachel’s insights about the main character’s struggles to rise above the temptations of street life were sage and certainly her own. She didn’t offer Claude Brown’s protagonist much empathy after his many missteps, but instead referred to him as a loser. During class, she never read aloud and always remained silent when called upon to answer questions. I soon stopped asking.

At lunchtime, Rachel avoided the cafeteria and stood alone at the end of the hall leaning against a wall. I repeatedly invited her into my classroom to sit, relax and eat. She always shook her head side to side. Our school has an internship program to reengage our disengaged students, providing them paid work experience in our building. With Rachel in mind, I created the position of English Department Assistant, a student who would help me each day during lunch with clerical and cleaning duties. She accepted.

I purposely ignored Rachel, to give her space while she wiped down the desks, swept and made photocopies. Occasionally I asked her thoughts about the music I was playing and she offered her opinions. Soon, she began to pull up songs and punk bands to listen to while she worked. When Green Day’s “Warning” was streaming through the Smartboard speakers, she stated “This is difficult to get through on guitar. Plus,” she continued, her own guitar “had seen better days and didn’t allow for a proper 6-string tune up.” She spoke as if I was already aware that she played. I responded as such and was able to get a generous friend to donate a Fender Telecaster to her. The first thing she did after playing the Vintage White Tele at home was to paint it gray. Rachel soon began to arrive at school early so I could lock her guitar in my closet and store it until the end of the day, when she would stay after school with Principal (and gifted musician) Mr. Brown for lessons and jam sessions.

Rachel remained focused during her lunchtime English office assistant job. But while she worked, it also became a time to share music, ideas, thoughts, books, wisdom, information and pieces of herself. I learned that her favorite TV show was The Walking Dead, she went to church on Sundays, didn’t like Fox News, and found people who curse too much boring. Her subtle wit added much flavor to these conversations. “Nice shirt Mr. Gabay. Did you get it at Baby Gap?” was a typical, and welcome, slam.

For Halloween, Rachel dressed up as Sasha from The Walking Dead and recruited me as Rick and 6’6” basketball Coach Mr. Zollo to be a zombie. She was proud that she replicated these costumes by precisely sewing and ripping to authentically recreate the characters’ outfits. Rachel certainly didn’t crave attention, but as she was a natural performer her theatrical side eclipsed her shyness.

During the spring semester, Rachel signed up for theatre class with Ms. Perez, who challenged her to cultivate her dormant talents. Although she sat hidden by the bookshelves at a desk that she placed in the corner of the room, Rachel bloomed in theatre class. She wrote stories, one-act plays and monologues, and she acted, directed and did set design. She performed in class and on the auditorium stage and, once again, cast Mr. Zollo, me and even a few of her peers in her productions. (I was fired from both for laughing: once during a scene at a Russian bar and again as a survivor of a plane crash.)

Pilgrims on our way

Rachel’s overflowing artistic momentum continued throughout her second and final year at the school. The hallway wall where she had once lurked alone during lunch now displayed an inspirational futuristic mural with a purple globe painted by Rachel.

Rachel resumed her job as English department intern assistant and worked with me during lunch where we continued our daily dialogue. She spoke about her love of learning and her dislike of school due to social anxiety. She was forthcoming about how her issues manifested as years of habitual absences, which had almost forced her to drop out. Regarding mental health, Rachel was very self-aware about the need to overcome her internal obstacles but, was uneasy with her few attempts at seeking clinical treatment. I listened and pointed out that at this school, she was the person who was “a doer, not a talker, a practice-er, not a preacher, and someone who puts her unique and positive beliefs into her behaviors.”

In late May, a month prior to graduating, she appeared with a book in hand, Indications of Apprehensiveness by Rachel Renee Wright— her book just released through Amazon. The novel chronicles the life of an awkward 17 year-old girl named Alex as she fights her way into adulthood. In the book, she describes Alex as a tomboy, punk rock lover, artist and nerd with dreams. At one point, Alex says, “I think each human being is weird in their own way and that’s what makes them themselves.”

By the end of her final year of high school, Rachel, the former voluntary mute, was our valedictorian, addressing the entire graduating class of 2016 in a packed, cheering auditorium. Wearing sunglasses, she offered the following:

As many of you know, I’m the mysterious kid that pops up in hallway corners wearing attire that looks stolen from a rock & roll-themed thrift store. I never enjoyed school, but this didn’t stop me from doing the work that had to get done. During my time in school I also had time to think about what is important and what is superficial. Reality can sometimes be harsh! What I’ve concluded is that each of us graduates have responsibilities. Surely we all know that education will not fix everything, but it is alarming that teens are dying at a rate that surpasses senior citizens. So it is hard to talk about a future when we are not even guaranteed one. Just because there may be something wrong with part of this generation doesn’t mean that you are part of the problem. The only thing for sure is that we are here now and we have today. Think about your future and remember that, in the end, you define you.

Your Voices Will Be Heard

From over twenty years teaching in New York City schools, I know that students such as Rachel Wright may be too untrusting to express themselves, but nobody is too quiet to feel. Whether you look for them or they seek you out, there are always students who need that little extra effort to help them reveal themselves to the school. I didn’t help Rachel become who she is; I simply found a way to encourage her to share her gifts. An educator’s job is to reach and teach, and it’s important to remind ourselves that there is always a song for someone.

Using songs as text as a way to connect students with literature and as a way to get to know them keeps me relevant and effective at my craft. Maybe U2 wanted the same for themselves when they gave away their Songs of Innocence album. The band might have fallen short of their original expectations, but they unwittingly achieved something even greater: connecting a recluse student and a rock & roll-loving teacher in the forgotten NYC neighborhood of Brownsville.

About the Author of “The Miracle of Joey Ramone” – Lee Gabay

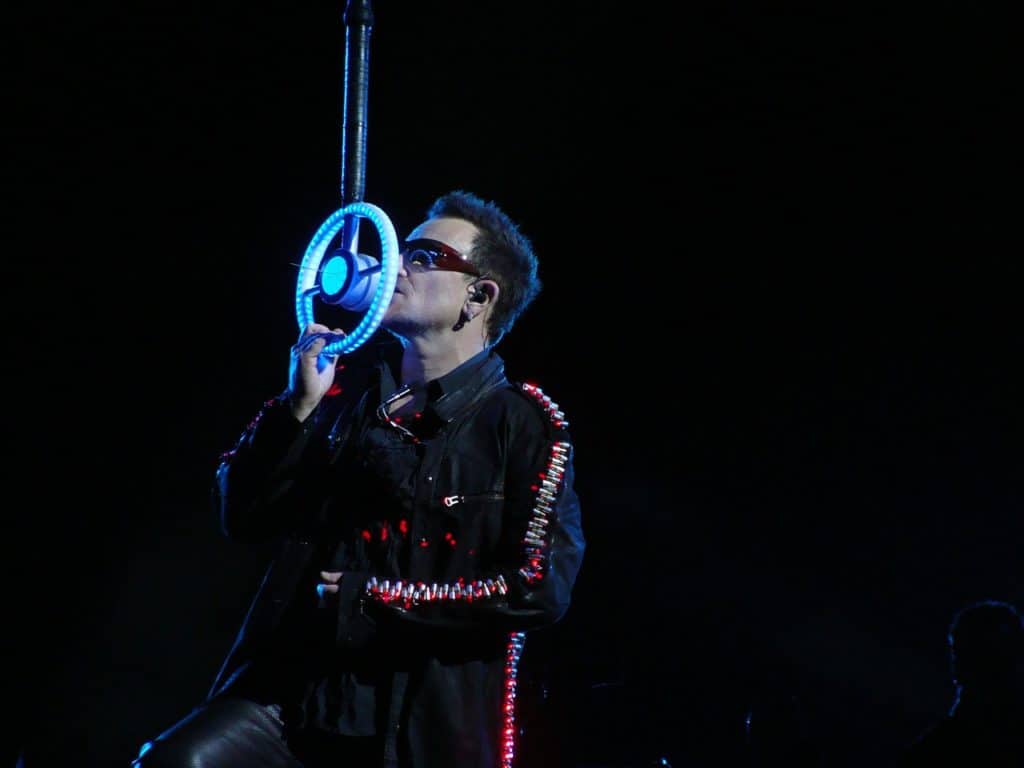

Lee Gabay is a doctor of Urban Education and a longtime New York City public school educator who currently teaches English at the Judith S. Kaye Transfer High School in Spanish Harlem. His research on Juvenile Detention Education is documented in his book, I Hope I Don’t See You Tomorrow (2016). Lee’s articles about education, incarceration, basketball and sneaker culture have appeared in Slam Magazine, Bleacher Report and other publications. In 2016, The New York Times named him a ‘New Yorker of the Year’. In addition, Lee has attended almost every U2 concert at Madison Square Garden since 1987.

Did you like the non-fiction piece: “The Miracle of Joey Ramone”? Then you might also like:

Dreamers Writing Prompt Generator

Experience the power of simplicity with our unique writing prompt generator. Designed for writers who crave spontaneity and surprise, our tool delivers one meticulously crafted prompt at a time.

Top 25 Most Popular Manga Right Now

If you’re searching for the most popular Manga right now, this top 25 list is the ideal starting point, whether a beginner or enthusiast.

To check out all the non-fiction available on Dreamers, like “The Miracle of Joey Ramone,” visit our non-fiction section.