Our Institutions

– Nonfiction by N. R. Robinson –

First Place Winner of the 2020 Dreamers Stories of Migration, Sense of Place and Home Contest.

Over the last twelve months of life at the Alvarezes, from fall of ‘65 to fall ‘66, the seasons gained momentum. The autumn equinox passed. Scornful rain, heavy rain, shy and intermittent rain fell down and laid on the ground. In a Rip van Winkle-ish déjà vu, WTTG Channel 5 began broadcasting third anniversary images of the Kennedy assassination. All the while Grandma Alvarez threatened to ‘put us away’ at the orphanage. The way she’d put Mama away at Saint Elizabeth’s, is what I thought. It was, Grandma said, our backtalk. It was me booted out of Saint Martins’, expelled. It was Cookie growing sadder and harder as the year crawled by. Since I kept to myself, even I didn’t know how I felt. Boy was I surprised when Grandma made good on her threat.

The early AM buzz of the doorbell must have woken everyone, except Grandma. As Cookie and me rushed to answer her urgent call, Grandma was waiting in earnest. Afterwards, everything moved in triple time, like a broken clock whirring fast: the two uniformed policemen who stood in the vestibule with an anonymous-looking lady in a heavy winter coat; Grandma declaring, “Their clothes in them bags”; the extended household watching or listening as the lady scooped up the wrinkled Safeway sacks stuffed with our belongings; Grandma pleading, “Lord ha’ mercy, take ‘em, I can’ stan’ they mess no mo,’” as the policemen ushered me and Cookie from the house; me, thinking, But we haven’t had breakfast yet; in the backseat of the police car, Cookie crying because, as much as she hated Grandma’s, the orphanage had to be worse; the five minute beeline to our next destination—a right from Randolph then straight down North Capitol Street to a rough-hewn, concrete-block-of-a-building just a penny’s pitch away from the U.S. Capitol dome. The sign read: DC Women’s Bureau.

Once again, things were no longer as they had been.

The policemen escorted Cookie and me past a linoleum-ed sign-in area and through a steel-grey door that leads into a cavernous space that seems higher inside than the building is outside. Set in the middle of the space is a desk at which two uniformed, female guards sat nursing cancer sticks and flipping through magazines. The women looked otherworldly, maybe because of the shrouds of cigarette smoke curling over and around them. The walls of the stadium-ish space were lined with dozens of metal doors, each with a grilled twelve-inch square cut at eye-level. From the squares, women’s voices leapt and bounced off steel and cinderblock.

“Look’it dem kids.”

“Heeeeyyyyy dahlins!”

“Oh, dey so cute.”

“Bring them up hea’. Le’ me giv’em some suga’.”

“I’m getting’ out soon, let me know if dey need a mama.”

The anonymous lady hustled us into a cramped, bare, back office. “The girls are easily excited,” she said. “Y’all hungry?”

We chewed on waxed paper-wrapped baloney and butter sandwiches. Cookie was glum. I took the lead, answering every one of the lady’s questions honestly and to the best of my ability:

“She eight. “We call’er Cookie but ‘er real name’s Karen.” “I’m ten.” “Nick.” “R-O-B-I-N-S-O-N.” “Mama’s name is ‘Madeline,’ she locked up at Saint E’s.” “Earl.” “I dunno whea’ Daddy at.”

At the end of what turned out to be our initial intake interview, the lady told us, “Don’t worry, y’alla gonna’ be arright.” She never told us why she believed we would be.

The next events unfolded in a series of flash-forwards: the lady bundling us up and out to her car, flipping on the brights then speeding down North Capitol, into the New Jersey Avenue Tunnel, up onto the Southeast Freeway. As we started over the Anacostia River, I began to feel the familiar anxiety; by the time we hooked the right onto Nichols, my head was beginning to pound. When we topped the crest and I saw the brick wall, I began to cry, quiet-like. The lady, I was certain, intended on committing us to Saint E’s, with Mama and the crazies. But we drove by the first gate, and the second, then further, until Saint E’s stretched wall of misfortune lay behind us, a ribbon waving in the rear window of the anonymous lady’s automobile.

We jolted on down Nichols, driving deeper into southeast DC than I had ever been, past a run-down nail salon, a corner Esso station, and a castle-like building fronted by a battered sign that read “Congress Heights Elementary School,” across Sheppard Parkway and past Hadley Memorial Hospital, which abutted a broad expanse of forest on our right. When unending forest suddenly sprung up in place of the avenue upon which we were driving, I glimpsed a sign planted to the right, at the lip of a virid valley. The only words I caught from that sign were the last part of an address—NICHOLS AVE: We had reached the end of Nichols; we were, literally, at the end of the road.

We turned right and plunged down an asphalt gash cutting through a wooded bowl then climbed and crested a plateau upon which sat a single-street cruciform village seeded with densely packed brick houses with angled roofs. When we pulled up at one of the house fronts, a large man came bounding out. I was dragged, wailing, by him from the car as Cookie’s cries faded, along with the rumble of the anonymous lady’s automobile into the enormous night.

The man, all big teeth and clodhopper feet, took his time yanking off my coat and shoes, shirt and pants. He shoved me, clad only in socks and briefs, into a tiny box-like room (the worse thing imaginable for a claustrophobic boy like me) reeking of the same shitty-pissy-Pine-Sol-y smell I had come to associate with Saint E’s. A sign that read “Time Out” had been tacked above the metal door. He calmly explained through the food slit: “When you quiet down, I’ll come get ya. Rules an’ Procedu’as.”

Wedged with me in that converted utility closet was a pee-stained mattress and caged ceiling bulb illuminating a furious history splashed across scuffed and dented walls: a festoon of dripping dicks and swollen breasts, hairy pussies and stick figures doing their business with each other, all incised (I imagine) with hidden safety pins or pried-off zipper tabs.

“Where am I? What is this place?” I shouted.

“Junior Village, T Roosevelt Cottage,” the big teeth man said through the door. “For boys wit’out no family.”

***

There is little left today of the original intent of Junior Village. The unconverted land and buildings are used by Job Corps, a government-sponsored cost-free education and vocational training program designed to prepare indigent youngsters for the outside world. Appropriate, perhaps, considering the general unpreparedness of the original institution.

Junior Village’s predecessor, the privately-owned Industrial Home School for Colored Children, had sprung to life during practically prehistoric times, back in 1848. Located in a craggy valley at the edge of DC, the School’s mission was to support the children of the free coloreds who had tried and failed to support them. Those colored kids humped and scuttled their way through institutional life: sewing their own clothing, planting and harvesting their food, helping to construct their U.S. president-named cottages with an industriousness that hurdled two half-centuries – through slavery and the Emancipation Proclamation; past The Great Migration and The Great Depression, the Great Wars I and II – until the DC government purchased the School in 1948 and rechristened it Junior Village. By the time Karen and I arrived in 1966, the original eight buildings and eighty children had morphed into the largest orphanage in America, a sprawling crawling-with-kids complex whose population of still mostly black boys and girls ranged from three to four times the two-hundred-and-forty-child capacity.

***

True to his word, the man, a T Roosevelt’s night counselor, came to collect me after I willed myself to stop wailing.

I would come to find that the short-staffed group of counselors operated as their own bosses. The best liked were (black) family men with kids and car payments. Because this bunch wanted their lives uncomplicated, there was an unwritten agreement between them and the boys. The guy who would become my favorite counselor, hip Mr. Sheffield – who, with his brown billy-goatish face and Fu Manchu mustache, looked like Jesus – put his side of the agreement this way: “Boys, this is my life y’all fucking wit’. Don’t make me have to fuck wit’ yours.”

The boys felt the same.

A second group, the Liberals, were (white) university graduates with hippie haircuts and thumb-grip handshakes. Supporters of civil rights, their goal was to untrivialize us: We had a History we were accountable to, and they tried to tell us about it.

The thing is, most didn’t care about their History. They cared about their Todays, all monotony and misery. So, they bushwhacked the Liberals. They filched their cigarettes and billfolds. They ignored the counselors’ entreaties to transform, to read and write and ‘rithmetic their way out of poverty. Most of those men slunk away, taking jobs where they could participate in the Struggle, but at a safe remove from T Roosevelt Cottage boys.

The third group was a scourge, mostly night counselors (black and white). These oligarchs of discipline, men who despised and loved us (they professed, grinning like crocodiles), stripped misbehavers naked and locked them in Timeout until they pleaded for release; prescribing Thorazine syrup for the recidivists until their limbs trembled and speech thickened. The chronically disobedient were hauled away to Receiving Home and incarcerated with young stick-up artists and murderers.

After these encouragements, some boys were sufficiently motivated to give or accept from a night counselor a quick blowjob or a poke in the clothing distribution room. And because fear was currency at Junior Village, victims morphed into victimizers. Love at that place seemed a complicated thing.

A natural timidity was all it took to get the blood of the cottage’s young victimizers-in-training boiling. Then weeks of baiting-probing boy-targets; “Show me that tongue” or “Lookit that ass” sotto voce, menacing grins, a meaningful smack on the buttocks, and if no retaliation, assault a formality: trapping the faint-hearted asleep in their bunks; the savage gang rapes called trains: the piccolo-ish screams and the thick smell of spunk and shit and gall in the air, the relationships of ‘protection’ that followed. In the language of yard sales, the boys-turned-girlfriends were a lay, a hump, a piece, as in, “You wanna piece a dat?”

That first night at T Roosevelt, the big teeth man led me into a dark dormitory stacked with thirty-odd bunk-beds stuffed with wheezing, snoring humps whose legs and feet protruded from the same chintzy sheets and blanket I carried, fifty-odd boys all tightly packed together, flesh and blood matches in a matchbox. Their sleeping clamor was not so much background noise as it was the character of the place. “Get ta’ bed,” the man ordered, nodding toward an empty top bunk. “Orientation tomorra’.” His eyes crawled all over me as I climbed up and onto the bare stripped mattress.

As his steps receded and ricocheting blackness swam around me, I lay limp and slack-jawed, trying to compose myself. I did what I had not done in ages—I prayed, fervently, eyes open, watching the mighty undulating night fall through the mullioned windows and bounce from the stilted bedframes. I mouthed the Lord’s verse that Mama, Cookie, and me, beaded rosaries in hand, prayed bedtimes.

Now I lay me down to sleep,

I pray the Lord my soul to keep,

If I shall die before I wake,

I pray the Lord my soul to take.

I prayed and watched the night rebound from the institution-white walls, the battleship-grey floor, from the Celotex drop-ceiling before slamming, a black broadside, into the double-decker bed in which I laid. As that place, Junior Village, wrapped itself around me, I prayed and fought the arousal of what Mama called Nicky’s Fits; familiar bands binding my chest and restricting my breathing, a curtain of haze I knew, from experience, would soon fall and drape my world until I awoke, soiled and with a chunk of time lost.

Desperate for distraction, I thought of Cookie. Where is she now? Was someone doing to her what the big-toothed man had done to me? And what about Mama – could this be what she endured? Had she overlooked the clouds of cataclysm gathering? Was she shanghaied like us, stuffed into the backseat of a car then shipped, bewildered, to Saint E’s? Was she stripped, caged, and forced to lay in darkness like me?

I felt a temblor of a memory shake my consciousness: the wooden voice of Mama’s doctor at Saint E’s, master of his voodoo psychoscience, advising Grandma, “Your daughter has textbook schizophrenia.” Stiff words, blasting, along with a thick Vitalis smell, from his open office into the hallway where Cookie and me sat, waiting: “Children have as much as a forty percent chance of inheriting the disease. Another contributor is childhood trauma.”

Like Mama, Cookie and I had experience aplenty with childhood trauma. Sitting at my writing desk more than forty years on, I think back to the rock-and-a-hard-place years at the Alvarezes. I wonder at the similarities of the trinity of our government-sponsored lives at those personal and politically hazardous institutions: Grandma’s house, Saint Elizabeth’s, and Junior Village – three hermetic places of confusion and disorder, monotony and madcap-ness, hysteria and suicide and lust. Out of this tsunami of sensation, how could something majestic arise? Even as a child, I asked myself some ill-formed version of this question.

Emerging from reverie to the Now of Junior Village, the raptus returned: a dry sandpapery mouth, the nausea under cold sweat and air so thick and soupy that no matter how deeply I breathed I could not get enough. I summoned forth a memory of a sixth-birthday incident. I casted back into time.

I saw a boy, a not-frequent playmate, standing opposite me in the gloaming of the horseshoe-shaped alley behind our I Street apartment. I was reliving our trifling disagreement: me pushing back, the flurry of our knobby fists, the thunderbolt of the half-brick slammed above my temple, the warm viscosity flowing as I staggered home to Mama. I endured the sirened drive to the alcohol-scented hospital and felt the white-coated stranger sewing my head-wound shut. Then, back home with Mama tucking me into bed, head throbbing, knees scuffed and burning. I heard her murmuring, “Sleep, baby. Sleep.”

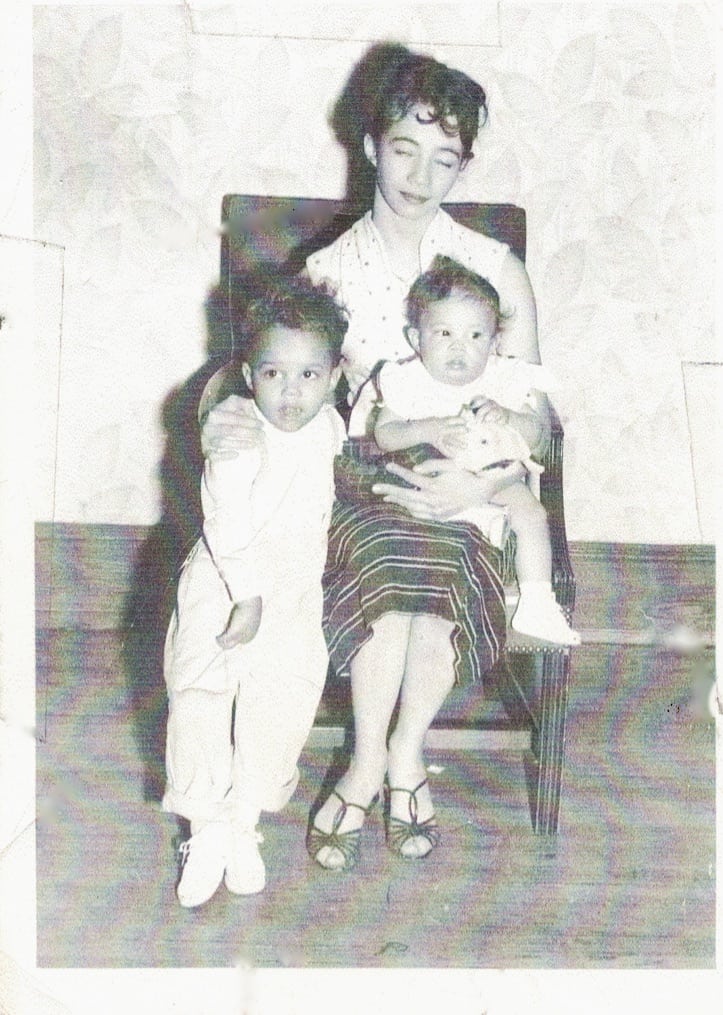

I woke the next morning to the sound of birds fussing in the trees outside. My eyes squinted against a sun bleeding around and under the tattered shade and across the island of my bed. Given the intensity of the rays, I knew it was well past the time Cookie and I usually left for school, past the hour Mama left for work. Mama was sitting on the edge of my bed, smiling; her fingers gently stroked my cheek. Cookie, leaning in Mama’s lap, stared into my face.

I was aware at that moment that all my hurts had disappeared. The two people I loved most in the world were in the room with me. I smelled their soapy skin; heard their voices, whispering. I felt their bodies bending the mattress; Mama’s gentle caress. I wanted to hold these precious seconds in time forever. Staring up at Mama and Cookie, their faces floating like cotton candy clouds doing a gentle dance, I could not have expressed it. But, looking back, I somehow knew that whatever happened, this moment in time was happiness.

About the Author – N. R. Robinson

N. R. Robinson grew up in Junior Village, a Washington DC-based, government-run orphanage that was the oldest and largest institution of its kind in America. A ninth-grade dropout, N. R. earned a general equivalency diploma and graduated from the University of the District of Columbia. In 2006, he left an executive position at Microsoft to begin the thirteen-year journey of scribing his coming-of-age memoir, Our Family Walks. A graduate of the creative writing programs at Florida Atlantic University (2009, MFA) and the University of Missouri (2016, PhD), N. R. is currently an Assistant Professor of English at Claflin University. As someone who couldn’t write a lick before graduate school at fifty, N. R. takes pride that four of his manuscript chapters were recognized as 1st Runner Up, and finalists in eight national writing contests over the last eleven months: including first runner up in the New Orleans’ 2019 Words and Music Creative Nonfiction Writing Contest and finalist in Sonora Review’s Nonfiction Contest, ENCOUNTER; The Tucson Book Awards, nonfiction category; the Columbia Journal Nonfiction Contest; the Hunger Mountain Creative Nonfiction Prize; and The Southampton Review Frank McCourt Memoir Contest. N. R.’s work has been published or is forthcoming in Dreamers Magazine, Iron Horse Literary Review, New Ohio Review, Santa Fe Writer’s Project Monthly, Quarterly, and Annual Volume 1 among others. He was a contributor at the 2015 through 2019 Bread Loaf Summer Writers’ Conferences, the 2016 and 2019 Tin House Summer Workshops, and the 2019 Kenyon Review Summer Workshop. He recently signed an Author Agreement with Miriam Altshuler of DeFiore and Company Literary Agency and can be contacted at nickrobi@hotmail.com.

**This story by N. R. Robinson received first place in the 2020 Dreamers Stories of Migration, Sense of Place or Home.

Did you like this story by N. R. Robinson? Then you might also like:

Bread Knife

Gelato and Frost

For David

Recovery

One Cut at a Time