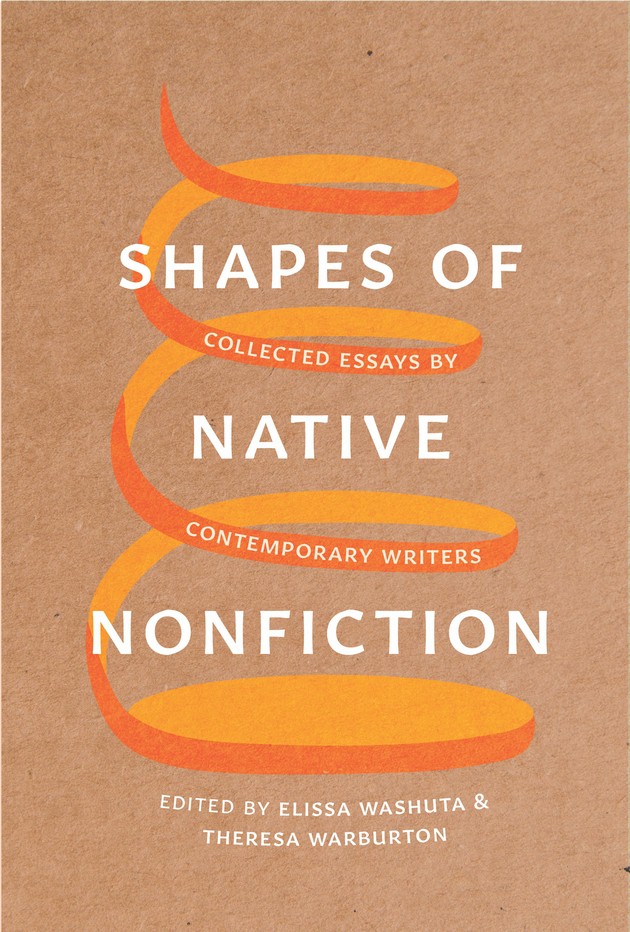

Shapes of Native Nonfiction an Outstanding Collection

Book Review by Carole Mertz

University of Washington Press, 2019, ISBN 9780295745763, 266 pages, $29.95

Shapes of Native Nonfiction delivers 27 lyric essays from 18 indigenous authors. The essays are grouped into four sections—technique, coiling, plaiting, and twining. These derive from basket-making concepts and give the collection its structural cohesion. The authors, either Canadian or U.S. citizens of tribal groups, bring their writings to the reader in unique lyrical essay forms. Some are part-memoir, some part-history of their communities, and some part-lament. To this reviewer, craft, and the manipulation of the essay form, is as important as content in the outstanding writing presented here.

While I find pain in this collection, I also find sincere writing that immediately displays high levels of essay craft, offered with abundant variety. Some of the assembled authors twine two or more themes into cogent unity; some invent other coherent forms using segmentation, some write laments, some present folk lore, some memoir. Often content is pungent with particular flavors of uprooted peoples, but that said, the authors select personal styles that go beyond ethnographical writing. As Stephen Graham Jones declared in “Letter to a Just-Starting-Out Indian Writer—and Maybe to Myself” (p.31 c.f. ):

“You don’t have to be able to define what an Indian is in order to write ‘Indian.’ If you are Indian,…then whatever you do, that’s Indian as well. You can’t not do it. It only messes up your writing to try to adopt a persona or put on a headdress to write. When you do that, your voice will probably get all noble and stoic, and then, yes, you may as well be falling dead off the back of a horse. Where you’ll land will be a John Wayne movie. And that’s a bad place for an Indian to have to spend forever” (p.36).

To bypass merely cultural reporting was, in fact, a goal set by the editors of Shapes of Native Nonfiction, as expressed in their Introduction. The editors refer to form and form-consciousness as the “work of the imagination, bringing order, intent, and interpretation to the raw material of remembered experience” (p. 11). In their selections, supported by the creative writing evolving from the Institute of American Indian Arts, they seek to move beyond an ethnographic method, allowing writers to be subjects doing the speaking, rather than subjects being spoken about. They are concerned with how Native authors “use form to offer incisive observation, critique, and commentary on our political, social, and cultural worlds rather than only relegating their contributions to descriptive narratives of Native life” (p.14). In the following paragraphs, excerpts from various essays will let you sample the variety of essay shapes used as you witness the high quality of writing appearing in this unique volume.

In her particularly inventive “The Trickster Surfs the Floods,” Natanya Ann Pulley tries to “map the space between the stars” (p.119 c.f.). She creates a trickster she names “Ma’ii” that helps her try to reconcile her teacher’s understanding of history with her own. “I tell a story that makes sense of my own self that is birthed from a truth of me,” she says. She reminds her teacher that she is a good storyteller, that she knows things. But “Ma’ii must have taken my words. Must have taken her ears. Must have taken the phone and made the calls to my parents…Must have chopped up the long threads of the language they were speaking into bits of laughter.” To the author, the laughter becomes the sound of gurgling water coming from the principal’s office.

Kim Tallbear, associate professor of Native studies at the University of Alberta, writes unusual and daring descriptions in her essay, “Critical Poly 100s” (p. 154, c.f.). She shares how she began writing 100-word pieces to make place / body connections. She defines this as “openness to multiple human loves and/or to deep connection with…the lands and waters of our hearts and with different knowledge forms and approaches that enable us to flourish as Indigenous peoples.” She likes open boundaries between “so-called science and so-called traditional knowledge.” Her mini-essays (embedded within her overall essay) include poetic descriptions of a high order and reveal a mind freed from conventional restrictions. “A million crisp stars hung silent in blue-black depths. Zoom in: planet, city, flesh. We are noisier—mouths co-mingle laughter, syllables, breaths. Warm fingers shed cocoons: touch,” she writes in “IceCity” (p.161), the essay that records, in effect, a coital encounter.

“Tuolumne” depicts author Deborah A. Miranda’s experience at the time her father is released from San Quentin prison. She writes of how her grandfather took her father to the river and of how the river assumed special significance for her father, especially at the point of his death. Grandfather and father seem incapable of having a father-son relationship. The river provides, however, a deep, but wordless connection. Miranda is a member of the Ohlone-Costanoan Esselen Nation in California. She is professor of English at Washington and Lee University. One can easily assume the actual writing of “Tuolumne” gave solace to the author.

One of the most painful writings included in Shapes of Native Nonfiction comes from Michael Wasson, in “Self-Portrait with Parts Missing and/or Smeared” (p.149 c.f.). This essay provides the profoundest use of metaphor encountered herein. It divides into 12 small segments, each titled with the small letter “i”. A classmate asks him why he has no father. He is ten years old. In other segments he’s 25 or one day old. The final segment gives the answer to his classmate’s question. It reads: “There’s an animal inside me, he says. He pulls the trigger.” The reader readily discerns the inner “storm” the author experienced as he traversed from the first segment to the last.

Bojan Louis writes a quasi-travel essay, “Fear to Forget & Fear to Forgive” (p.89 c.f.). In it he reveals the extreme anxieties he has experienced. “We all live with fear,” he states, “the US, it seems, as a nation, more so than any other. I’ve spent the majority of my life within its confines: an Indigenous ward in an occupied land. We’re afraid of Black people, Muslims, Mexicans, China, Russia, North Korea, the Middle East, Africa, Cuba, greasy food and being fat, being too skinny, being wrong, being right or righteous, being accused of being politically incorrect or correct, of teenagers (especially Black teenagers, teenagers of color), of bees or the lack of bees, of not enough people liking our status updates, of reading and critical thought, of not reading enough or of what we read, of thinking for ourselves, of understanding.” In his observations, he accomplishes self-understanding and the determination to channel his anxieties into meaningful product.

“The three months we spent in Southeast Asia were…a traumatic experience, no thanks to my verbal assaults, inability to control my emotions, and substance abuse.” But by writing through his passages, the author confronts his violence and becomes “present to his pain,” acknowledging that he wants good over evil and knowledge over ignorance. In spite of struggles, the writing will be enough, he affirms, and implies it will help the healing process, a tenet of the very magazine in which this review appears.

I urge readers to be willing to overcome the pain they fear they may encounter here, for Shapes of Native Nonfiction is a collection that broadens one’s understanding of human suffering and of the impulse that counteracts damage and drives writers toward the healthy process of new creation.

About the Author – Carole Mertz

Carole Mertz, Book Review Editor for Dreamers, critiques poetry and prose for various literary journals, including most recently at Eclectica, Mom Egg Review, and South 85 Journal. Her recent poetry is at Muddy River Poetry Review, Front Porch Review, The Ekphrastic Review, and elsewhere. She assessed poetry submissions to Women’s National Book Association’s 2018 Poetry Contest and is advance reader in poetry and prose for Mom Egg Review. Carole resides with her husband in Parma, Ohio, where she teaches music to young children.

Did you like this Book Review by Carole Mertz? Then you might also like:

Sam sax’s Madness Under Examination

Take a Does of Michael Pollan’s Latest Batch, How to Change Your Mind

Through, Not Around: Stories of Infertility and Pregnancy Loss

To check out all the book reviews available on Dreamers, visit our book review section!