Someone to Watch My Back

– Fierce Fiction by Alice Campbell Romano – May 27, 2018 –

Our mother had a tattoo. We didn’t see it until we washed her before the undertaker came. It was two tattoos, in truth. Two brown dots, one above her right breast, one below.

***

Ten years ago, I was twenty, home for the summer before my junior year at the University of San Francisco. Mom roped me into coming with her to the Santa Monica police station to pick up my sister—for any influence I might have over Bibi. Bibi was fifteen. Bibi didn’t listen to anyone.

Venice Beach is a scruffy blot on the coast. Body builders; sellers of junk T-shirts and jewelry; tattoo parlors, and the stink of skunkweed.

One long-haired dude had even pitched a lean-to on the sand where he did business. The police had him under observation; they needed proof he was selling dope. It was mostly kids who ducked in and out of the tent; some lingered. No one turned him in.

I saw the dude skateboarding a couple of times, when I brought visiting family to savor the sinful shores, but he never registered as more than a guy with good legs and a pony tail. Black hair, deep, dark eyes. A nice face, not hard. Looks, however, are not always an indication of character. The guy rolled gently down the sidewalk, those tanned thighs angling below worn cut-offs, eyes prowling the crowd for an easy mark he could lure into his tent.

I was thinking: My stupid sister.

“Mom, he’s really nice. I mean, we talk about Salinger. Not just Catcher in the Rye, but about the man, Salinger, and Franny and Zooey, and stuff. I mean, these books are assigned in school, I’m supposed to learn about them.”

“He’s a bum. And this is not about him. Not as far as I’m concerned. It’s about you, the mess–”

“He’s NOT what you think. He’s just, he’s a… oh, Mom, I can’t talk to you!”

We were in the cop shop on metal chairs in a bare, beige room, waiting for the officers who’d corralled Bibi after she’d ducked out of the dude’s tent. We’d been given only the sketchiest of explanations on the phone, and I surmised the officers were listening to us, hoping Bibi would say something that would compromise the guy, such as, “He only sold me one lid!” But with Bibi, Mom’s interview skills were pitiful. Mom and Bibi could never communicate with each other, not even when Bibi was an infant. Mom offered her breast, Bibi spat it out. At five, I was feeding formula to my newborn sister. So, I thought I’d give it a shot:

“He looks nice. If he’s that skater guy I think he is.”

No answer. I tried a lighter touch. “If he IS a beach bum, at least he found the showers. Bibi, I mean, if he’s not selling dope, why is a clean-looking, well-educated, young man wasting his days in a lean-to on Venice Beach?”

“Not everybody has to conform, but the fact is, I think he had a hard time with his family.” She stopped. Silence fell, except for hollow echoes from somewhere in the cop shop.

“Ah,” I breathed, using my best big-sister-as-counsellor voice, “is that something you can identify with?”

She shook her head, in a teenage you just don’t get it way. Her pink, slash-cut bangs parted, revealing brown roots; her hair was growing out, a month’s worth, maybe. How had I not noticed? And she wasn’t wearing that ghoul eye make-up. Just a little lip gloss. She grinned at me: “What are you, my freaking shrink?”

Mom was watching us, clueless. She reached out a hand, but Bibi sprang from her chair and twirled around to confront us, her face alight, as if to tell us something vital. Her tank top shifted as she spun, and we caught a glimpse of a tattoo on her shoulder blade.

“Oh, my God, you have a tattoo! Oh, my God!” Mom looked as if she’d been drained of vital fluids. She folded, so her head almost touched her knees. Her fists pounded her calves as she keened, “Vile…disgusting…”

Bibi was at the door in a shot. She tugged it open but hopped right back, startled. We weren’t locked in—but we might as well have been: outside the door a tall, frizzy-blonde policewoman loomed, bulging in all the places the uniform is not designed to flatter, cop paraphernalia dangling, her expression a hard don’t you dare! She pulled the door shut.

Bibi was at the door in a shot. She tugged it open but hopped right back, startled. We weren’t locked in—but we might as well have been: outside the door a tall, frizzy-blonde policewoman loomed, bulging in all the places the uniform is not designed to flatter, cop paraphernalia dangling, her expression a hard don’t you dare! She pulled the door shut.

Mom was on her feet now. She strode to Bibi and gripped her upper arms. The words ground out of Mom’s throat, a gravel whisper:

“Have you no self-respect? What are you?” Mom’s voice began to rise. “Arrested at the age of fifteen.”

“She hasn’t been arrested, Mom. Detained.”

“You! Shhh.”

Then, to Bibi, as she stroked Bibi’s tank top: “Desecrating your sweet body. Show me.”

It must have been the word “sweet” that did it, but Bibi softened, tugged her shoulder strap and turned, so we could see the mark on her back. Mom sucked in her breath.

“Oh, my dear little girl.”

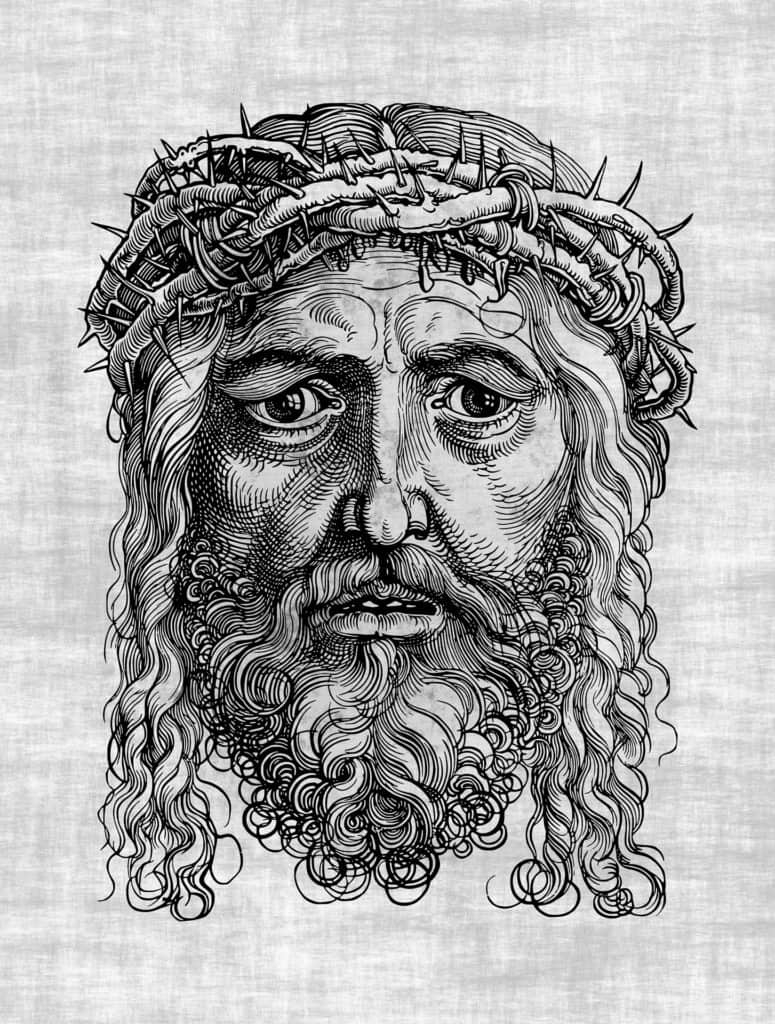

My little sister, my iconoclastic, foul-mouthed rebel of a baby sister had the face of Jesus tattooed on her shoulder. It was a beautiful tattoo—and I don’t much like tattoos. Mom and I both saw this for what it was – a work of real art, a copy of an old master, a gentle, loving, forgiving Christ on my sister’s back…

“…To remind me He loves me, to protect me.”

Mom: “How long have you had it?”

Me: “It’s beautiful.”

Bibi: “You really think so?” Her face was shining. “Mommy, I’ve been a real bitch to you. I want to talk to you about stuff, but you always want to correct me. I’m not doing dope or buying dope or anything like that. If they’d found any dope on me, I’d be arrested.” She fell silent, and we didn’t know how to fill the silence.

Mom put her arms around Bibi and pulled her close. Then she drew her toward the wall and gestured her into one of the corner chairs. Mom took the other. I left the room. This, at last, was their time.

***

“I always wondered,” Bibi was saying. “When I got picked up by the cops? And you left the room? How’d you get past the Amazon? You know, Brunhilda guarding the door?”

The first thing we’d done was to close Mom’s eyes. Bibi placed two fingers on Mom’s left eyelid and I put my two on her right lid. In one voice we said, “Go in peace, Mom. Good night.”

We were grateful for the rubber pad and the half-sheet under her. We soaked washcloths with warm water, washed between her legs and threw away the cloths and the soiled half-sheet. Then we sponged the vomit off her chin and neck and peeled off her short nightgown.

The home hospice nurses had given us a list of what to do if she should die when they were off duty. Even if they’d been there, Bibi and I would have chosen to perform these final offices for our mother. I’d been away—off and on—for so long: college; a job in another country; an unsuitable man; and now home with my baby sister to see Mom through to the end.

We were awkward, Mom and I, even at the end, never intimate. Funny. Funny peculiar. I would have thought warmth, intimacy of the heart, relaxation, would be a corollary of personal care. I told her I loved her and that she was a wonderful woman who had done everything right with me, but I don’t know if she believed me. She and I couldn’t just let it all hang out; she was too—what? Proud? Insecure?—and the circumstances, even with in-home hospice care, were dreadful.

She’d taken the cancer diagnosis with grace. She hadn’t cried or complained. The day after she’d had the first operation, she went to her Church group. Oh, it’s nothing, they got it all, just a lump. She never did tell Dad, even if she could have tracked him down in Thailand with his latest paramour.

As she lay dead on the bed, I became aware that her right breast didn’t flop skinny to the side as did the left. Astonishing what a great job the surgeons did reconstructing it; you’d never have known when she was dressed. Appearances mattered to Mom. I was glad we were there for her now, to spruce her up, comb her hair, wash under her arms.

“What are these? Moles? They’re not dirt.”

Bibi gave a soft chuckle. “Remember how stoic she was? No tears? Everything’s going to be fine, it’s not my time, all that, remember?”

“Yeah. Soldier on.”

I was in my last year of college when she was first diagnosed and wasn’t expected to drop everything to be with her – I mean, the prognosis seemed so good. But she must have been afraid. She’d have said she didn’t want me to worry. But I was realizing in these sad weeks of her dying that I felt short-changed: couldn’t she have talked to me? Or: couldn’t I have talked to her? Why didn’t she let me put my arms around her and feel her close? Why didn’t I just do it? She was so damned brave! I supposed she hadn’t broken down with Bibi either, even though Bibi was still home during that time of diagnosis and treatment, struggling through high school.

Then Bibi told me what Mom had admitted: that on the first day of radiation, the technician had tattooed two dots on her chest so anyone in the future would know the parameters of the beam that was meant to save the breast.

Mom didn’t shed a tear when it turned out the tattoos were for naught; radiation couldn’t save the breast, but the surgeons promised they could reconstruct the missing tissue, and there was every hope the cancer would not return.

Until, of course, it did.

“Oh! The Amazon! That big blonde cop at the door. In Santa Monica. The day Mom lost it over your tattoo.”

“Yeah. That cop was badass, but you just moseyed out of the room.”

“Nah. I told her you were innocent, and I was your sister and I was heading home. She caved.”

Bibi smiled. She patted my leg. “I’m really glad you left Mom and me together.”

Together wasn’t a word for our family back then. Troubled might begin to cover it. Dad was gone; the breakup was nasty, although a long time coming. I’d run off to San Francisco to be brilliant at college, and Bibi had failed almost everything at SaMoHi. Mom was holding it all in. Soldiering on.

Is it any wonder Bibi hung out at the beach? She engaged in risky behavior with dopers and cons who saw her as needy, easy prey. She didn’t want to become one of them but going home to Mom was hard because Mom criticized. Your hair, it’s ridiculous. Those clothes, you look like a slut. You missed tutoring again. I’m paying for that, young lady, and you had damn well better pass those re-entry exams, etcetera, etcetera…

Is it any wonder Bibi hung out at the beach? She engaged in risky behavior with dopers and cons who saw her as needy, easy prey. She didn’t want to become one of them but going home to Mom was hard because Mom criticized. Your hair, it’s ridiculous. Those clothes, you look like a slut. You missed tutoring again. I’m paying for that, young lady, and you had damn well better pass those re-entry exams, etcetera, etcetera…

“See, when you left us alone at the police station, Mom listened to me. She heard me. She hated tattoos. I mean, like a real fear. She couldn’t understand how I could do it, but what made her listen instead of just yelling at me was, why a tattoo of Jesus? Mom hadn’t been to Church since before Dad left. She found her way back and I suppose those women in her reading group nurtured her. But my Jesus tattoo broke the ice between Mom and me.”

“Maybe I should have gotten one.”

“You’re kidding! She already thought you walked on water. Why can’t you be more like your sister… she does this, she does that…”

Wow. It took me a moment. I walked on water?

Bibi and I finished what we could do for Mom. At last, we pulled a clean, soft sheet up to her chin, keeping her arms outside the sheet and folded across her chest. She was only 56. Many women are beginning new lives at 56, while our Mom was lying dead. So much pain, finished. Everything finished. That’s nonsense about people looking like they’re sleeping. They’re far too still. They don’t breathe. Nothing twitches. Nothing. They’re dead. I shivered. Bibi and I had unplugged the space heater in Mom’s room and it was growing chilly.

We sat on the loveseat waiting for the hospice folks. They’d handle the rest.

“I think you intimidated Mom. You’re so smart, you do everything right. She was never sure of herself.”

I took a deep breath. I sat there for a moment, eyes closed. It was hard to admit, but I was learning. “I get that, finally. You were Little Miss Rebellion, but I was the one who didn’t understand…” I closed my eyes; shook my head. I was in for a lot of sadness and regret, but it wasn’t to heap on Bibi. I changed the subject. “You know, that day at the cop shop, I saw the dude, the skater. When I was on my way out. I guess they arrested him without your help.”

“He came in of his own accord. For me. He blew his cover.”

“He was a narc?”

“Oh, no. Jesse was a priest. He hung around Venice to keep an eye out for stray cats. It wouldn’t work unless nobody knew. He had to seem like this super cool dude. That was the con. Until you got talking with him, about, well, everything. There was a bunch of us. And over time, he brought us back to ourselves.”

I let her explanation sink in. “It wasn’t a cult thing? Like Scientology?”

“Jesse didn’t tell us to believe in anything but ourselves. That was the hardest part for most of us strays.”

“So why the tattoo?”

“So why the tattoo?”

“My idea. Kind of a stand-in for a dad, I guess. Someone to watch my back.”

“So, you and Mom? You stayed close.”

“We did. Hard to tell when she was in so much pain, and all the meds, but yes, we were good friends. She even told me a silly thing, something she was ashamed of. It was so…so Mommy.”

Bibi laughed a little, looked over at the bed, said, “It’s okay now, Mom.” Then, to me: “When she was lying flat on the table under the radiation cone, and the tech told her they were going to tattoo her chest, Mom cried. She said the tears just rolled down the sides of her temples. Just poured out. Mom was getting a tattoo and it bothered her more than getting cancer. She was funny.”

Now the tears were pouring out of Bibi. She sobbed, caught in the first wave of grief. She turned to me and we held each other until the doorbell rang.

About the Author – Alice Campbell Romano

About the Author – Alice Campbell Romano

Alice Campbell Romano is preparing a chapbook and poetry collection in a workshop led by New York poet Jennifer Franklin at The Hudson Valley Writers’ Center. She’s also deep into a novel at the Sarah Lawrence Writing Institute, based on a screenplay written with her husband Renato Romano. Alice has lived and worked in Rome, Los Angeles and New York; she continues to mine these places–and her life–at last able to give writing a goodly share of her time. This is the first short story Alice Campbell Romano has submitted. The prompt that started it allowed a melding of actual events, and an acknowledgement of how much we don’t understand about the people we love the most.

Did you like this fierce fiction story by Alice Campbell Romano? Read more fierce-fiction on Dreamers Creative Writing.