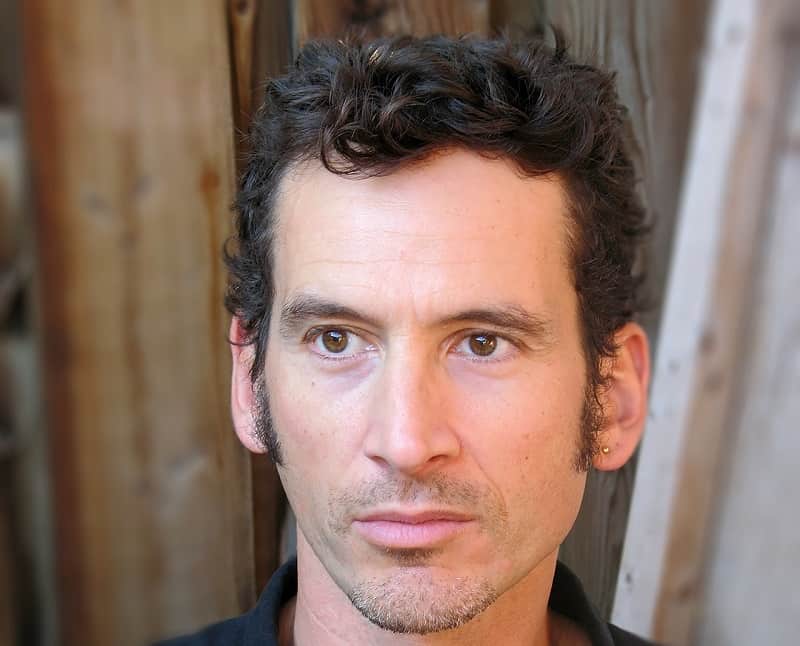

An Interview with Steven Heighton

An interview with author, Steven Heighton, featuring writing as re-enaction, exploring obsessions, and the night-mind.

In 2016, Heighton received the Governor General’s Award for Poetry for The Waking Comes Late. His most recent novel, The Nightingale Won’t Let You Sleep, is equal parts intimately personal and globally political, written in a smooth masterful prose that draws on his experience as a poet as well as a storyteller.

Throughout his work, Heighton manipulates emotions with the mastery of the literary greats. Every word and turn of phrase has been used to its fullest effect to build in layers of psychological, social and political meaning, revealing the best and worst of who we are as individuals, as communities, and as a species as a whole.

In this interview with Kat McNichol, Editor-in-Chief of Dreamers Creative Writing, Steven Heighton talks about writing as re-enaction, exploring obsessions, and the night-mind.

Steven, welcome to Dreamers!

Thanks, and congratulations on creating the magazine and the website. I edited a small literary magazine some years ago and I know how much work it takes.

Your most recent book, The Nightingale Won’t Let You Sleep, deals with themes of place and home, and the impact that a sense of belonging has on self-identity. These themes appear often in your work. Why do they arise so frequently for you?

I’m honestly not sure and that’s the way I like it. I don’t think it’s healthy for literary writers to over-scrutinize their own subtexts. I’ve written elsewhere that poets and fiction writers should not bother writing about what merely interests them, because interest is never enough. What merely interests you will probably bore your reader. What haunts and obsesses you might, with hard work, interest readers enough to hold their attention.

To be clearer: writers do need to locate their obsessions and know what they are, since that’s the material they’ll keep returning to. At the same time, they shouldn’t minutely dissect them such that at a dinner party they could explain logically to an academic why they write what they write and what they’re trying to say. If you can elucidate your work that way, you’ve killed the living mystery at the heart of it. And why write about it in the first place if you fully understand it? Good literary writing involves exploring obsessions you don’t fully grasp.

You’ve taught writing workshops to aspiring writers at such places as the Book House on Pelee Island, the Banff Centre for the Arts, Sage Hill Writing Experience, and many others. What do you enjoy most about instructing other writers?

I love leading group workshops because I find teaching exhilarating (also exhausting, which is why I’m glad I only do it occasionally). I also love the one-on-one discussions with individual writers, where I pore over their manuscripts with them and explain my messy marginal edits. I feel that in a one hour, face-to-face meeting, I can help a young writer more than in a whole semester of classes; I can explain what I see as their unique challenges and suggest specific, personalized solutions.

Tell me about your “Writing as Re-enaction” workshop. Why do you feel these re-enaction techniques are so important?

The basic difference between literary writing and everyday writing, whether an email or blog post or news story, is that the latter is simply trying to convey info in a clear, functional way. Effective literary writing, on the other hand, sonically embodies or “re-enacts” its material. Here’s an example.

Clear info: While I was standing on the edge of the plain, a bunch of noisy horses ran past.

Re-enactive writing: Galloping hoofbeats drum the rutted plain with thunder (that’s the Roman poet Virgil, in the excellent translation of Robert Fagles).

Anyway, in the workshop I illustrate the principles of re-enactive writing and then get participants to create an example of their own. In a sense, re-enactive writing is simply the verbal, acoustical version of the “show, don’t tell” dictum that every creative writing course urges.

Reviewers of your work often reference the quality of your character development and your skill at representing the multi-facetted reality of human psychology.

How do you create characters with so much emotional depth?

I guess I just try to inhabit my characters and to go deeper into their minds and hearts with every draft. And I make that necessity possible by ensuring that my characters all embody at least an element of my own psyche, however small. That element is the conduit that allows you to enter the discrete loneliness of this stranger you’ve created, and then—by adding qualities you’ve seen in other people, or read about, or simply imagined—to grow the character into a living composite.

Do you have any advice for writers working on emotional characterization?

Look for the central contradiction/contradictions in the person. Because that’s what character is. If your novel requires an angry, domineering, alpha female boss and you simply insert an angry, domineering alpha plucked from central casting, all you’ve got is a type, a caricature, a cartoon, a cut-out. You need instead to figure out what the boss’ contradictions are. Everybody is something but also something else. Your character doesn’t emerge, and the story doesn’t start, until the word but appears. Aurelia, the boss, was always losing her cool and hollering at everyone, but sometimes, at lunch…

How has your experience as a poet enhanced your prose writing?

It’s enhanced it simply by making me more sensitive and attentive to language. But there’s also a drawback. A poet is cursed with a poet’s ear, which means that at times a poet writing prose can be too attentive, too fussy. To be sure, there are points in every story or novel when the writing should aspire to the condition of poetry, at least in terms of precision and richness. But there are other times when it’s perfectly fine to write a more relaxed, less fastidious sort of prose. Alas, I can’t just dial down my poet’s intensity to some energy-wise green setting. Which can make editing a novel of a hundred thousand words a labour of loathing.

After you’ve finished a book, story or poem, and it’s been published, do you ever look back and wish you could change anything?

Sometimes, sure, but mostly I shrug it off and move on. Every book fails; “finishing” a book means you got to the point where you were unable, or unwilling, to fuss over it anymore and decided it was time to move on.

Having said that, I should admit that in 2013 Palimpsest Press re-issued my first book, the poetry collection Stalin’s Carnival. It first came out in the spring of 1989, when I was 27. In preparing the reissue, I cut a bunch of weak poems and, in the ones I kept, cut some unnecessary words, or improved them, or tweaked line breaks or punctuation. My rule was that I could make small superficial changes but could not alter the fundamental spirit or tone of a poem. If I couldn’t live with a poem on that level, I cut it.

You spoke of your night-mind in an article for CBC. Tell us about that. Have you dreamed anything new lately that you’ll be writing about in the future?

Dreams are—in this society, nowadays—a badly overlooked form of inspiration. Your night-mind will, at times of psychic upheaval or spiritual growth, generate lots of vivid and visionary dreams. At such times you’d be a fool not to attend to them on personal grounds—and if you’re a creative artist, you can draw on them creatively as well. With your overthinking day-mind off duty, your night-mind is able to speak with great clarity and power. And if you’re a light sleeper and wake up often, you’ll recall a lot of those dreams and should write them down.

As for the coda to your question: no, few dreams lately. I recently made some changes in my life and for that reason, I think, my night-mind has for now quit howling at me and cinematizing its advice and intentions.

Your work is always very carefully researched and factually accurate. What processes have you followed when conducting research for a novel or story?

I do what I call retro-research, which is a way of saying I do little or no research before I start a book. If I get inspired by something—say, the deserted city of Varosha, Cyprus, which was the starting point for my recent book The Nightingale Won’t Let You Sleep—I’m too eager to get to work to spend much time on research. It would feel too much like being back at school. So I do the bare minimum I can get away with, then just trust my instincts and let the story write itself. Once I’m done, of course, I need to check and see where I got it right—and wrong. And I do check. Whether I’m searching online or consulting experts in certain fields, I make sure I nail the facts as necessary.

Have you ever faced writers block? How do you deal with it?

Never. I’m a full-time writer. If I don’t write, I don’t eat. And for years I had a family to support, too. The need to make a living by my pen has been a powerful dis-inducement to writer’s block. Every day I get to the desk for a little or a long time. Every day I try to write something: maybe just a paragraph, maybe a number of pages.

Of everything you’ve written so far – story, poem, song, novel, article, etc., which is your personal favourite and why?

It’s a good and valid question but for me impossible to answer. For one thing, I’m not looking backward that way—I’m looking ahead. My “favourite” piece of writing—and at the same time my least favourite—is whatever I’m working on now.

You write in a wide-variety of styles and genres from poetry to non-fiction to short-stories to novels. How have you been able to move between genres and styles so successfully?

Right from the start of my writing life, when I was at university in the 80s, I found myself drawn both to lyric poetry and to short stories with a strong narrative drive. Those two related, but also very different, impulses still drive me today. Moving back and forth between the forms has always felt natural to me. If my poems were more narrative and my narratives more poetic, maybe the commuting between forms would get more confusing and the forms would start to merge. But, for me, they’re still really distinct, so little confusion or convergence occurs.

We met during a writing retreat at the Book House on Pelee Island. While there, you spoke of your songwriting aspirations. Tell us about that.

I wrote songs as a teenager and young adult. Awful! Derivative! Affected lyrics, conventional chord progressions… But for the last few years I’ve been writing some rhyming poetry suitable for lyrics, and when I tried to set those lines to music, better tunes and chord sequences came. At least two of the songs came out of dreams, by the way; I dreamed a few lines and a tune, got up in the night, picked up the guitar, and the song came.

In 2015, you spent a month on the Greek Island of Lesbos helping with the refugee effort.

Can you tell us about your experiences?

I’m now writing a book about it. I think it’s about two-thirds done—though I could be wrong about that. I usually am.

What turned thinking into action for you?

I hate to sound like a broken record, but it was a dream. It occurred to me that I should go to Lesbos to volunteer. I decided to sleep on it, and then in the small hours my night-mind offered its opinion, in no uncertain terms. I woke up, went to my desk, and logged on to a travel site to find tickets.

Would you do it again?

In a heartbeat. But I need to find the right window. In November 2015, I was between drafts of The Nightingale Won’t Let You Sleep, my daughter was away at university, our dog was old and no longer needed a lot of walking, and I’d just received an advance for the novel, so I had more money than usual in my account. Note my privilege here: I went to Lesbos because the time and circumstances were right for me. Refugees, of course, don’t get to choose. They just flee. And I really want to emphasize this. My volunteering was at most a small sacrifice on my part, not a large one.

Have you found writing to be healing? For example, has writing helped you to process your experiences on Lesbos, or any other important experiences in your life?

If you’ve located your material in your obsessions—as opposed to mere interests—the work will always be cathartic, hence healing. But as for my volunteer experiences, the need to heal is not something that a middle class, physically healthy Canadian should come home and talk about. After all, I have a home to return to (after a mere month away). The refugees truly were—are—homeless, risking their lives to find asylum and safety. Many are still trapped in camps in Greece, like the one I worked in. How impertinent and grotesque it would be to describe my Lesbos book as personally healing.

I’m not sure I agree with you, although I do understand what you’re saying. Canada is a wonderful country. We’re lucky to live in a place where so many cultures and belief systems are able to co-exist relatively peacefully. I agree that it’s important that we understand our privilege and not take the quality of our lives for granted, and we also should do everything we can to help people in situations like the one you experienced on Lesbos. That being said, your own sense of healing, growth and understanding as a result of the pain you observed, and also likely experienced, is something I believe you should express. I disagree with you when you say that “the need to heal is not something that a middle class, physically healthy Canadian should come home and talk about.” If you need to heal, no matter who you are, you should talk about it. There should be no restrictions on this. In our society, we’ve stripped emotions from most facets of academia, business, and research. We’ve also learned to feel guilty when we experience emotional pain. But the reality is that all of us, even privileged white Canadians, need to talk about how we feel – what makes us sad, what makes us happy, what we’re scared of. In today’s turbulent political climate, the kind of writing we need is the kind that reaches underneath our identity labels. The world needs more vulnerable, empathetic perspectives.

You told me that in Lesbos you held the hand of a woman who was unconscious. You watched over her alone while the other volunteers were busy dealing with other recent arrivals, including her family. I bet there are a lot of emotions connected to that moment for you. I believe that telling your personal story about that experience could help people look beyond the political rhetoric to empathize with the refugee situation at a human level, you know what I mean?

You write that if people need to heal, they should talk about it. I feel that they should be able to talk about it but not obliged.

But maybe we’re saying the same thing here in different ways.

As for that moment with the woman in the transit camp, I do include it in my Lesbos book. And you can imagine some of my emotions at the time: anxiety, for one, because I’m no paramedic. I do try to convey those emotions in the writing. And you’re absolutely right: a personal experience like that, vividly recreated, will help people “look beyond the political rhetoric to empathize … at a human level.” Which is the main purpose of the book.

Still, it’s important to me that I not turn an act of bearing witness—an act which will inevitably have some effect, maybe a healing one, on me—into a mere occasion for personal transcendence. In other words, I can’t let the suffering of others serve mainly as a conduit for my own healing. I feel my Lesbos stories and associated emotions should not eclipse but instead footlight and focus the larger events and sorrows I’m depicting. I don’t deny that my actions might have been personally healing—and I do touch on the matter in the memoir—but my own needs can’t and won’t be the main event.

And isn’t it possible that when we subordinate and sublimate our own needs, through acts of service, we heal in a deeper way than if we set out with the express purpose of healing? Well, maybe that depends on the person and the situation. I can’t speak for others. I’m not even sure I can speak for myself, in the sense that I’m not yet sure what I think. Certainly this idea might not appeal to, say, a single mother who has done nothing but attend to the needs of others for years.

One more thing about that moment in the medical tent: as I sat there, I recalled that the last time I’d sat beside an unconscious female patient, the woman in question had been my mother, on her deathbed. And I do make that connection (indirectly and subtly) in the scene. Subtly, because I’m hoping that my emotions—and any healing involved—will serve as a subtext, a quiet murmuring under the surface of the narrative instead of a howl of grief and pain that would drown out the voices and stories of the book’s heroes: the refugees and certain other volunteers.

When we last spoke, you were working on a children’s story told from the perspective of a stray dog living among refugees in a refugee camp. Can you talk about the inspiration for this story?

The inspiration was Kanella (“cinammon” in Greek), a stray dog who found a home in the camp. I figured that writing about the crisis as perceived through the innocent (if at times mischievous) eyes of an animal who knows what it is to be homeless might be a good way to introduce children to some of our world’s harshest realities.

On Pelee Island, you talked about playing soccer in Lesbos with a group of boys who had just arrived from Syria. This story moved me more than I can say. Can you share that story here? What did this experience mean to you?

Here’s an excerpt from my work-in-progress:

Ten minutes later I approach one of the large tents. Many of the Syrians are just inside, sitting on chairs or on the sleeping mats, some eating, some lying down, but several families are sitting out on the plank benches against the tent’s white plastic walls. A number of them tilt their faces, eyes closed, toward the low but warm winter sun . . . In the mouth of the big top I hold up the ball and call out, “Anyone want to play?” Instantly three children leap up and start toward me—a boy of around twelve years old, another around ten, and a girl of six or seven. We set up in front of the field-kitchen trailer. For a net, I propose a portable steel crowd-control fence; the two boys mime that they consider it rather small but it will do.

Initially the game pits the two smaller kids versus the elder. I play keeper for both sides. I’m no soccer player and have little idea what I’m doing. They do. Even the little one can kick with some force, albeit little accuracy. It’s the middle boy—the ten year old, in his blue T-shirt and with his spirited, almost taunting, grin—who can really play and can drill his shots just where he wants them. The three race around in front of me, the girl falling a couple of times, crying momentarily, getting up and rejoining the game. Behind them the parents have emerged from the tent to join the other refugees on the benches, where they sprawl in the sun, the men smoking, all watching with faint, fatigued smiles. It hits me that the children, too, have just crossed the straits from Turkey on a dinghy steered by a refugee who might never have seen the sea before this morning. Their resiliency may have more to do with youth than ignorance; they have no idea what they’ve just survived; they must feel their parents would not have led them into dangers that they, the parents, could not surmount. As for the steersman appointed by the human smugglers—in the kids’ eyes he too would have seemed a capable adult. Or have such delusions already been demolished, at least for the oldest of the three? He has a face crowded with years—with care and evolved character—not the face of a child of eleven or twelve.

Now the boys stage a three-way penalty kick competition, creating a penalty kick spot in the gravel, fastidiously placing the ball on the spot before each kick, then quibbling with each other’s placements and arguing about whether a shot that smacks the edge of the fence has scored or hit the post. I don’t understand the words but it’s easy enough to follow the objections and negotiations and I participate with great pleasure. The kickers cheer loudly when they score. They score a lot. Occasionally a couple of the parents clap or laugh briefly as well. Larry stands watching, now and then calling out “Careful now!” to the kids when they slip on the gravel, and to me as well—“Careful of your back, Steve!” The deft ten-year-old head-fakes before he shoots, a teasing smile on his face while I grin back, crouched low in what I hope is a fair facsimile of a real tender’s stance.

[ . . . . ]

By one p.m. the sixty Syrians have boarded an idling bus and a handful of volunteers stand in the dirt of the lower parking lot to see them off. The ten year old boy in the blue T-shirt, sitting on his mother’s lap, has pressed his face to the window and keeps grinning and waving at me. He’s holding one of the red, heart-shaped balloons which we handed out to the children as they boarded; someone in Holland has mailed a thousand of them here. I lose sight of the mother and son, then there they are in the open doorway of the bus. He waves again, I wave back, and then he leaps down and runs toward me with the balloon on its string flapping over his head like a pennant. He stops in front of me, offers his small hand for another formal shake, then with his other hand proffers the balloon, saying something brief and insistent. There’s no doubt about his meaning. Again imitating the Muslims who’ve thanked me for one thing or another, I put my left hand over my heart (should it be my right?) and accept the gift. “Shukran,” I say. He turns and runs back to the bus that’s rumbling, quivering, as if with impatient readiness, the mother in the doorway beckoning as she happily scolds him, Come, my love, hurry!

Now—February 2019—I wonder if they even made it out of Greece and into Macedonia before that border and others to the north crashed closed. With luck, those three are now kicking a ball around on a windswept pitch beside the Baltic Sea, or they might be stuck—interned—in one of the growing, weltering DP centres in northern Greece. If so, their prognosis is poor. In camps in Lebanon, Jordan, and elsewhere, legions of second- and third-generation refugees sit trapped, citizens of limbo with no rights but to remain incarcerated in perpetuity—a fact so troubling that the mind refuses to stay in the same room with it for long. To preserve sanity—or just equanimity, functional comfort—the mind recoils and turns to more agreeable considerations or, at best, problems that are easier to contemplate and possible to solve.

Wow, Steven, my heart is pounding. Thank you for sharing that story.

What advice would you give to new writers?

The same advice I once gave myself when asked by a magazine, The New Quarterly, what tips I’d send back in time to my younger self, if I could. These “memos” became the basis and first chapter of a book of memos on creativity I published a few years ago called Workbook. Here are some of that first set of seventeen:

- Interest is never enough. If it doesn’t haunt you, you’ll never write it well. What haunts and obsesses you into writing might, with luck and labour, interest your readers. What merely interests you is sure to bore them.

- Let failure be your workshop. See it for what it is: the world walking you through a tough but necessary semester, free of tuition.

- Embrace oblivion. The sooner you quit fretting about your current status and the long shot of posterity, the sooner you’ll write something that matters—while actually enjoying the effort, at least some of the time.

- Allow yourself to enjoy it. Squash the temptation to accentuate, poeticize, wallow in the difficulties of the writing life, which are probably not much worse than the particular difficulties of other professions and trades. Take a tradesman’s practical approach to your development: quietly apprentice yourself to language and the craft, then start filling up your toolbox, item by item, year after year.

- Ignore Byron, who wrote that “We of the Craft are all crazy.” He was largely right, of course; ignore him anyway. To romanticize the Writer as pursued by furies, enthused by Muses, beset by demons—this is nothing but professional self-importance and self-pity. Writers have no monopoly on poverty, humiliation, self-doubt, or aggressive inner demons. Close your door and get on with it.

- Momentum and enthusiasm can mean pretty much the same thing. When working on a longer project, ruthlessly guard and prolong the momentum.

- In writing, as in life, “personality” is not character. Never try to be cute, to be winning, to audition for the reader.

- Never try to be cool. A writer afraid of seeming square will never write anything truly cool. The purest definition of cool, after all, is not caring what people think.

- Stand on the side of artifice—of worked and earned, elaborated form. Life gives us enough of life. We approach art for something different: more distilled, catalyzed, charged, and signifying.

- Stop straining to be “original” and, with luck and applied time, it just might happen.

- You can only write authentically within the bounds of your own sensibility, but you can read and appreciate far beyond them. To develop a broad and generous vision, you’ve got to.

- Careerist writers don’t have friends, only allies. This is reason enough not to be careerist.

- Careerist writers don’t confront and relish challenges, they crash into obstacles, which they naturally resent and fear. This is reason enough not to be careerist.

- There can be just one final arbiter of your work. Refuse to appoint anyone else as your judge and appraiser, executioner, potential approver—the one reader, fellow-writer, critic, editor, or publisher whose acceptance of your work will stand as an ultimate verification, a proof of arrival, relieving you of that impostor-feeling that every artist knows. (A feeling that signals only that your esthetic conscience is still active.) Resign yourself to the road, there’s no arrival. There’s no map either, come to think of it, but the sun is rising and the radio is on.

With thanks to Steven Heighton for conducting this interview with Dreamers!

If you enjoyed this interview featuring Steven Heighton, consider becoming a Dreamers Magazine Subscriber. We publish a new author interview in every issue. Become a magazine subscriber today.