The Prisoner: Free at Last

– Fiction by Phil McNichol – April 11, 2018 –

I met a man once who said he had spent his whole life in prison. He said it was the only place he could remember ever having lived, until the day he found freedom. That’s the way he put it: he didn’t say he had broken out of prison, or got released after serving the time for whatever crime he had committed. He said he “found” it, like it was something he saw lying around and just picked up.

He was an odd duck. We met in a bar on the edge of the desert. It was a simple, “clean, well-lighted place” like Hemingway described in his short story of that title. He just picked up his drink and sauntered over to my table. He said he was in the mood to tell me his story, as he plunked his glass of beer down, and pulled back a chair. The bartender, who had been wiping the counter like he had been doing it forever, suddenly stopped, looked over and caught my eye.

The man across from me reached over and patted my right arm. “It’s okay,” he said, “He’s been here before.”

I assumed he was talking to me; after all, he was looking right at me when he spoke those words. But the bartender shrugged his shoulders and resumed wiping the already quite clean, brilliantly shining counter. It was as if he was responding to what the freed man had said. He was a regular, but it was my first time. My car had broken down in the desert and I had walked, and walked, praying that I would find someplace where I could get help. This was many years ago, you see, long before the time of cell phones. So, I was a bit confused about who had been “here before.”

I assumed he was talking to me; after all, he was looking right at me when he spoke those words. But the bartender shrugged his shoulders and resumed wiping the already quite clean, brilliantly shining counter. It was as if he was responding to what the freed man had said. He was a regular, but it was my first time. My car had broken down in the desert and I had walked, and walked, praying that I would find someplace where I could get help. This was many years ago, you see, long before the time of cell phones. So, I was a bit confused about who had been “here before.”

The man, of indeterminate age, began telling me his story. As best I can recall this is how it went, but I will nevertheless revert to the first person:

“All I knew was this was the place where I had always been. I had no sense for a long time of being confined. Why would I? It was all I knew. I had nothing to compare it with; it was my world.

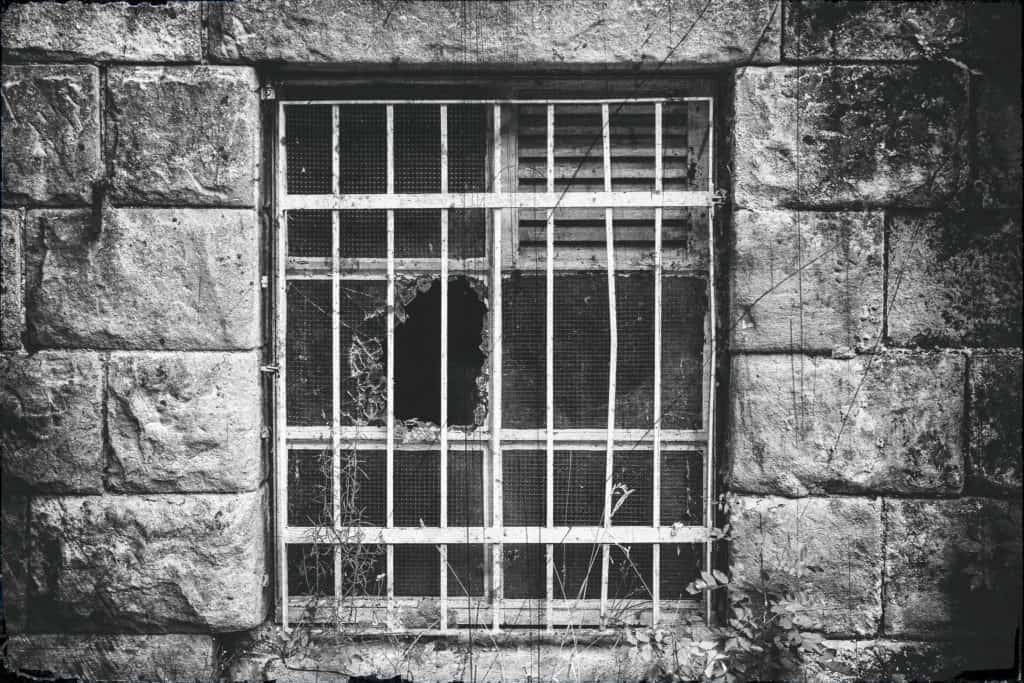

“I can still see it to this day as clearly as if I just left it: four bare, stone walls built of blocks, each of exactly the same size and mortared together tightly with great care and precision. There was what I now understand was some kind of window or airway with bars across. But it was too high up for me to reach, let alone look outside. No light ever came in there, or sound.

“There was an incandescent electric bulb high up on the ceiling. It cast a wan, yellowish glow characteristic of the type. It was apparently on some sort of automated track because it appeared out of the wall on one side, tracked across the ceiling, and then disappeared on the other side. A lot like the sun, I guess. I even slept and woke up according to the disappearance and reappearance of that dull light.

“I had a simple metal cot for a bed, a thin, foam mattress, a rough, grey blanket and a pillow. There was a hole in the floor which I instinctively understood was for relieving myself, at least that’s the use I put it to. Several times a day a plate of food would appear, pushed as if by magic under the massive, metal door that never opened. Likewise, once a day just before the light went out, a shallow basin of water, with a cloth and towel similarly appeared, and disappeared after I was finished.

“I think at some point I must have reached a level of consciousness about my situation and began to take stock of where I was. I had memories of being a child in that place, and a quite happy one at that. As I say, it was my world, and as everyone does at first, I found everything I needed to keep myself busy and occupied. I was in a state of wonder about being alive. I explored every inch of my world, and had a virtual map of the location of each little scratch or pebble of mortar that at some point in the history of the cell-world had fallen to the floor from above.

“Tiny creatures would emerge from time to time to feast on the crumbs that fell off my plate, and sometimes even fight little wars over them, much to my childish amusement, I confess. I even had my favourites, those I would cheer on in their courageous fights, or shed tears over if they should fall. But I never interfered, though at first I was sorely tempted. I became strictly an observer.

“So that was my life, you see, and for the longest time it was enough. I was happy, or so I thought.

“But then one morning when the light appeared as usual, I awoke with unusual feeling of unease and discontent. Something was wrong. For the first time the walls were closing in on me; I felt confined, imprisoned. I began to take stock of my surroundings in a systematic way, trying to get my bearings and understand my situation. It was a “hands on” exploration as well as a thoughtful one.

“And then in that process there happened a moment of significant insight, an epiphany, you might say.”

Those last few words were spoken in a suddenly much louder and defiant tone of voice, as he threw a look across the room at the bartender.

“Yes, yes, an epiphany,” he said, looking back at me, leaning across the table, close enough that I could feel his insistent breath on my face; “a great awakening, a realization that there must be something beyond the walls, an expanded universe, as it were, and freedom. I did not have that word for it at the time. But now I understand that’s when I first thought and felt with every fibre of my awakened self that there must be such a way of being, something other than being confined within four, stone walls.

“The great moment came as I traced a finger along the seam of mortar around a certain block of stone. I dug in a fingernail a bit and watched as little granules of mortar were dislodged and fell to the floor.

“And then it hit me, literally as a flash of brilliant light inside my head: I can do this. I can get out. I can find out what is on the other side of the wall.

“I twisted back and forth, and in a minute or so broke, a piece of wire off my cot and went to work right away dragging the sharp tip of the wire through the mortar around the block. I was excited, so excited; I thought that in a very short time I would dig all the way through the mortar, loosen the block, remove it from the wall, and then . . .

“But it soon became evident this was a much greater task than I could possibly have imagined. I now know that hours, days, months, years went by, and still there was no end in sight. Bit by bit I was virtually demolishing my bed by desperately twisting more pieces of metal from it to use as my Essential Tool. Occasionally, I despaired of my grand task coming to an end, of ever solving the great mystery of what was beyond the wall. And, I confess, I wept. But not for long. Truth is, I was driven, obsessed. I had to keep going.

“And then the moment came, with the latest piece of wire deep in the mortar under the block, I felt it move – ever so slightly, but move it did.

“Despite my weakened state after so much effort for so long, I felt rejuvenated. I summoned up a kind of super-human strength, digging my fingernails into the gaps I had made around the block and tried to pull it towards me. It wouldn’t budge.

“But I persisted. I couldn’t give up. Quite often I fell to my knees and beat my fists against that block. I managed to break off a thicker piece of metal from what was left of my bed to use as a lever to put under the block in hopes of prying it out. And it moved, just a bit, toward me. But it worked.”

He took a break from his narrative for a moment, just long enough to take a swig of his beer.

“Anyway,” he said, looking over at the bartender again with a bit of a worried look this time, “to make a long story short, and though it took a very long time again, I got that block out of the wall to the point where it was about to fall down to the solid stone floor of my cell.

“The moment of truth had arrived at last. I took a deep breath, summoned up all my strength again, said a word of encouragement to myself, pulled the block out of the wall, and nearly bust a gut lowering it down onto the floor.”

“What did you see?” I asked.

“Yeah, what did you see, wise guy? Tell him what you saw, as if I don’t know.”

That was the bartender. He had his right hand, palm open on his forehead, shaking his head, as he leaned with both elbows on the counter. “How long, dear God, how many times do I have to listen to this?” I heard him think, I swear I did.

“Hey,” the man said, touching my arm, looking at me earnestly, “don’t pay any attention to him. He has ears, but he can’t hear. But you can. I know you can.”

“But what did you see?”

“I saw nothing – just a black hole.”

“But still, I wanted to get into that darkness. I was curious; and maybe there was more to it than that. I had to find out. So, I started to climb through. It wasn’t easy. It was a very tight fit, and I’m not, as you can see, a big man, so I twisted, and I squirmed for the better part of the passage of the pale, yellow light overhead. In fact, it was about to go out when . . . well, if you were in my cell behind me watching you would have seen me disappeared into the hole in the wall up to my hips.

“But still, I wanted to get into that darkness. I was curious; and maybe there was more to it than that. I had to find out. So, I started to climb through. It wasn’t easy. It was a very tight fit, and I’m not, as you can see, a big man, so I twisted, and I squirmed for the better part of the passage of the pale, yellow light overhead. In fact, it was about to go out when . . . well, if you were in my cell behind me watching you would have seen me disappeared into the hole in the wall up to my hips.

“And then you would have seen me . . .” At this point I saw a look of what I can only describe as terror take over the man’s face, a frightened, horrified look.

His voice trembled, and his hands shook as he tried to lift his beer to his mouth for another sip as he said, “you would have seen me frantically trying to get out of the hole, back into the safe confines of my cell. You would have seen me finally succeed in doing that. And then you would have seen me, with super-human effort, lift that big, heavy stone block off the floor and put it back into the hole. You would have seen me push and push and push, until finally it was all the way back in. You even would have seen me pick up every little bit of broken mortar I could find and painstakingly put them back in place around the stone.

“And you would have seen me, out of breath, totally worn out, take several steps back to examine what I had done to make it look like nothing had ever happened; and to confirm that I had indeed accomplished that objective.

“And finally, you would have seen me stumble to the broken remains of my bed and its worn-out, long-suffering mattress, throw myself down on it, and fall into a very deep sleep.”

He picked up his beer, leaned back, and drained it.

“Is that the end?” I asked.

“No,” he said.

“No, of course not,” said the bartender who, much to my surprise, was standing at the end of our table. He put a comforting hand on the man’s shoulder. “You’d better tell him the rest. But he does have a tow-truck on the way.”

“Oh, okay. That’s alright, this is the best part.” The man said, taking a deep breath.

“So, like I say, I fell into a deep sleep that night. And I had a dream. In my dream I was walking through a lovely meadow of lush, green grass and wildflowers of all description and colors. I know, you might wonder how I would know all that, never having experienced anything outside my prison cell. I had no frame of reference. Point well taken. All I can say is it was a miraculous vision. The world that I had worked so long to discover beyond my cell walls was right there, in my dream. And I knew it, as if I had been there before, somewhere, somehow.

“And then I came to a stream of pure, clean water flowing through the meadow. And on the other side I saw and heard a group of people having a picnic. Never had I imagined there could be such a joyful scene, the happy laughter of men, women and children, singing, dancing, enjoying their feast under the bright warmth of a nurturing sun. After a few moments they caught sight of me, and many among them began to wave and call in my direction, beckoning me with open arms to join them in their happiness. I wanted to join them. I did, I really, really did. But for some reason I hesitated.”

“And then I came to a stream of pure, clean water flowing through the meadow. And on the other side I saw and heard a group of people having a picnic. Never had I imagined there could be such a joyful scene, the happy laughter of men, women and children, singing, dancing, enjoying their feast under the bright warmth of a nurturing sun. After a few moments they caught sight of me, and many among them began to wave and call in my direction, beckoning me with open arms to join them in their happiness. I wanted to join them. I did, I really, really did. But for some reason I hesitated.”

“Yes, you hesitated,” the bartender said, now returned behind his counter. “And you know why, don’t you: because you didn’t believe, because you were still locked up behind your infernal walls, weren’t you?”

“Yes, I suppose the great, the almighty bartender is right, as always,” the prisoner said, more than a little sarcastically.

“But I knew what to do, intuitively: there were stones scattered around in the field near where it sloped toward the stream. I began to gather them up, and at a certain place between myself and the river, I began to build a wall. ‘One last, great task you have,’ I told myself, ‘to be free, truly free. And then anything is possible.

“I built the wall of field and river stones high enough that it eventually blocked my view of the other side, where the happy people were beckoning me to join them.

“I stood back from it for a few moments . . .”

“And?”

“I, I walked right through it, as if it wasn’t even there.”

“But that was in your dream, right?”

“Well, yes it was; or not,” he said, pausing for a long moment, looking off into space before looking back at me to continue:

“Just let me tell you this: somewhere there is an empty cell. I am no longer there.”

“But, there’s a ‘but,’ isn’t there? Tell him about the but,” the bartender said, pausing in his work, staring off into space, as far as it went, anyway, in that small space.”

“Yes, he’s right again, our infallible bartender. There is a ‘but.’

“A happy ending of my story would be that I walked through the wall into the happy place.”

“So, where did you go?” I asked

“Here,” the man said, looking me straight in the eyes. “Here.”

“You mean this bar?”

“No, not this bar. Worse than that. Here. In this story. In these words. That hardly anyone will ever read. That will end up buried in ‘archives’ in the farthest little corner no one will ever find, trapped in cyberspace for as long as that moment lasts.

“No, not this bar. Worse than that. Here. In this story. In these words. That hardly anyone will ever read. That will end up buried in ‘archives’ in the farthest little corner no one will ever find, trapped in cyberspace for as long as that moment lasts.

“I walked into this toxic unreality. And so did you. And so did he, the ‘Creator’ over there, who can’t stop polishing his damned counter.”

“You’re crazy,” I blurted out, “I can leave here any time I want. I’ve got a car out in the desert. There’s a tow truck coming. Soon I will be back on the road on my way to my destination. I have a life.”

“That’s what they all say, isn’t it, Polisher?”

“Yeah, well, where are they, all those other people you told this same story to? Where did they go. They probably just got up and left, like I’m going to, right now,” I said.

And I did. I pushed my chair back so that it made a loud, harsh scraping noise on the stone floor. I went to stand up. He took hold of my arm, and held me with his eyes.

“They’re gone. I tried to warn them, but they wouldn’t listen. And now they’re gone. I mean gone, gone, as in ‘nada.’

“Want to know what I saw in that moment, that terrible moment when I first crawled through the hole I had made in the wall?”

“I think I know,” I said with a deep sigh of resignation.

“Yes, I think you do, and that is something worthwhile in and of itself, after all: to know the truth.

“But what I saw in that other awful moment was nothing, absolutely nothing,” said the man who had spent most of his life confined within four stone walls, the man who had spent an incredibly long time working to be free, the man who thought he was almost there, and more.

“Stay,” he said finally. “Have another beer. We’ll talk for a while, about whatever comes to mind.

“And He over there will polish his counter and think about what might have been.”

It could have ended there. But, fortunately, it didn’t.

I looked across the table at him, totally at a loss for words for a long time. But then I remembered that morning not so long ago when I was walking as usual down the road to our little farm in the woods and fields of our special place.

I saw near the roadside the moss-covered rock left thousands of years ago by the retreating glaciers. I went over and touched it for the first time, wondering what secrets it held. Walking back to the house I saw the early-morning sun breaking bravely through the late, autumnal clouds for just a moment. I didn’t bring my camera, so I promised myself I would let that light stay in my heart.

I saw near the roadside the moss-covered rock left thousands of years ago by the retreating glaciers. I went over and touched it for the first time, wondering what secrets it held. Walking back to the house I saw the early-morning sun breaking bravely through the late, autumnal clouds for just a moment. I didn’t bring my camera, so I promised myself I would let that light stay in my heart.

And then in that moment I thought of you, my dearest friend, my love, and what you said about the black-matter heart of the expanding universe not being something to regard with fear and trembling, but a . . . a place, for want of a word to describe the indescribable, where the spirits are gathering, as one and all. Not dark at all, but full of spiritual light.

“Never doubt that I am with you,” I heard you say again. And I wept unashamedly in remembrance of it. I wept for the loss of you, for your loss of this world you loved so deeply, and well. And I wept for the world.

And, strangely, some might say, those tears of grief and loss were also tears of joy. Finally, it was the laughter we shared together I remembered above all else.

I reached across the table and took the poor, eternally suffering man’s hand.

“Come with me,” I said, and he walked with me over to the bar.

“Come with me,” I said, to the old bartender, putting my other hand on his, the one that could not stop trying to find reality in reflection.

And we walked out of that place together, through the layers of confusion and confinement, into the heart of the ages-old rock, through a crack in the clouds where the brave morning sun was shining, into the great mystery of absolute joy.

Free at last.

About the Author

Most of Phil McNichol’s career has been in the news business. He worked as a journalist for more than 25 years and he’s been writing his award-winning weekly column Counterpoint for The Sun Times for 15 years. Phil has written extensively on local, provincial, and national politics, Indigenous rights, local and foreign affairs, agriculture, the environment, nuclear energy, ageing, literature, and his beloved little farm in Hope Ness. He now writes the popular blog, Finding Hope Ness. Oh, and we must not forget perhaps his most famous subject, “Mr. Massey,” his 1946 Massey-Harris 22 tractor.

Did you like “The Prisoner: Free at Last?” Read more stories on Dreamers Creative Writing.